Patricia Hendricks Sensei, a 7th Dan Aikikai Shihan, has been a prominent figure in the aikido community for over five decades. Her journey began in 1974 under the tutelage of Mary Heiny and Stanley Pranin. She then spent extensive periods training in Iwama, Japan, under Saito Morihiro Shihan, becoming one of his closest students and serving as his representative in the United States. I sat down with Patricia on one evening during the 14th International Aikido Federation Summit that took place in Tokyo in late September 2024 and I was absolutely delighted to find out that all of the good things I had heard about her over the years turned out to be true.

Guillaume Erard: Thank you very much for accepting to talk to me today. To begin, could you tell us how you got into Aikido, in what sort of context, and perhaps what were your expectations and your impressions as a beginner when you started?

Patricia Hendricks: Well I actually grew up in Atlantic City New Jersey and I was used to seeing entertainers, you know, Frank Sinatra and the Beatles and all that. My grandfather was a reservation manager in a big hotel, so we were in that kind of atmosphere, because it was Atlantic City before there were casinos. When I finished High School, I wanted to go to California, to UC Berkeley, but I knew that I didn't have a 4.0 GPA, so I had to go to a junior college first.

So I traveled nine months from the coast of New Jersey to California, I just put all my things in my car and I drove. I stayed in different places and on the way. I already had a kind of interest in martial arts, Bruce Lee and all that, which was just beginning to happen. I had a lot of adventures on the way but when I did get to California, I decided to settle in Monteray, which is one of the most beautiful cities in the world, actually. So I said "I'll just go to the junior college there and see if I can get a 4.0, and then I'd be able to get in.

I did it and I was able to to move, but the first the first semester that I was at Monterey Peninsula College, I took Aikido. I remember that Mary Heiny was teaching, she's a very famous Aikido person. I was always kind of gymnastically oriented and I was always really athletic. I did football, baseball, everything, you know, and so then I started doing Aikido and I just fell in love with it. I just couldn't believe how it was, I knew immediately it was the kind of philosophy I wanted to follow.

Then I met Stanley Pranin. At the time, I was involved with a women’s group, but I had heard about Stan and decided to check out his training sessions. It was in a garage, and when I arrived, everyone was already training. He was such a dynamic teacher—really full of energy—and I immediately thought, This is great! This is exactly what I want to do. I wanted to work with falls and more gymnastic movements. Even when I was just a fifth-kyu, I was already eager to test myself, jumping over four or five people and rolling on the other side. I had always been like that—kind of a tomboy. Because of this, Stan often used me as uke, and eventually, I became uchi-deshi. That was my first experience as uchi-deshi, and I think I spent about a year, maybe a little more, training intensely while also attending my college classes.

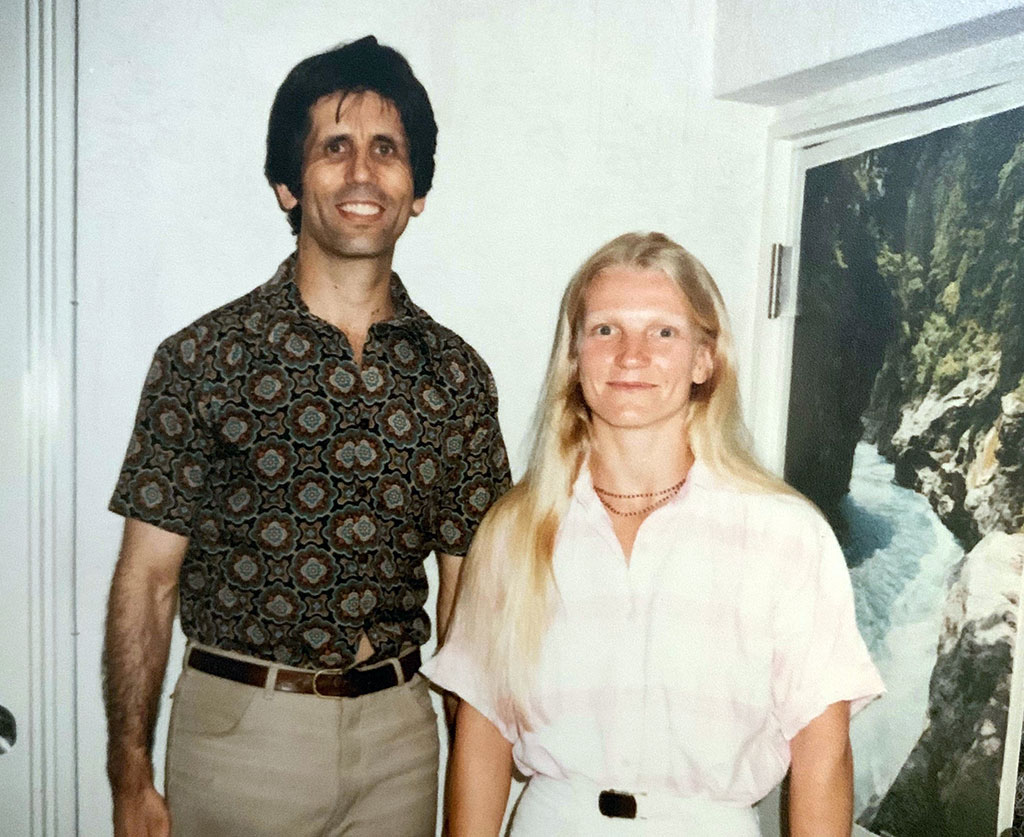

Patricia Hendricks with Stanley Pranin

Patricia Hendricks with Stanley Pranin

Then, coincidentally, Stan decided to move to pursue a master’s degree at UC Berkeley, with plans to eventually go to Japan. I told him, Well, you’re my teacher, and I actually want to go to UC Berkeley, too. It was a little early for my grades, so I went to another junior college first, earned a 4.0 GPA, and then transferred to UC Berkeley, where Stan was already studying. Eventually, he left for Japan, but before that, we trained at a dojo affiliated with Saito Sensei.

Guillaume Erard: So that connection with Iwama was already in place...

Patricia Hendricks: Yes, yes. So, Bruce Klickstein—who no longer does Aikido—you probably know his background...

Guillaume Erard: I do [Editor's note: In June 2013, Bruce Klickstein was arrested on federal charges of possessing, receiving, and distributing child pornography. He was indicted on three counts.].

Patricia Hendricks: He was teaching, and he was a great teacher in a lot of ways. Nobody really knew, and then what I saw at the Oakland dojo was that Bruce actually left to do a two-year apprenticeship with Saito Sensei. A lot of his older students went with him, and Stan was already there. I had already started at UC Berkeley, but I took a break and thought, "Well, I'll just go and see how it goes." When I got to Japan, I had already decided that I would probably take Aikido very seriously and that I would see if this was the right teacher for me. That was Saito Sensei. Within just a few months, I knew he was my teacher.

So, I decided that when I would go back to the US, I would focus on Japanese studies. At that time, it was called "Oriental Languages" with an emphasis on Korean, Chinese, or Japanese. I chose Japanese. But in the end, I stayed in Japan for about a year. Saito Sensei noticed that things were changing—he had never had a female student stay that long or take training so seriously. In fact, I was the only woman there. But he was an excellent teacher. He and his wife, along with the whole family, took me in as if I were one of their own. After a year, I could speak Japanese pretty well because there was no one else to speak to, so I had to learn.

When I went back to UC Berkeley, I continued training at the Oakland dojo. Bruce had returned by then, and Saito Sensei had already started using me in demonstrations. The odd thing was, he was an amazing teacher, but he didn't quite know how to teach women—he hadn’t done that much before. He would throw me a lot, and I was fine with it, and he knew I was.

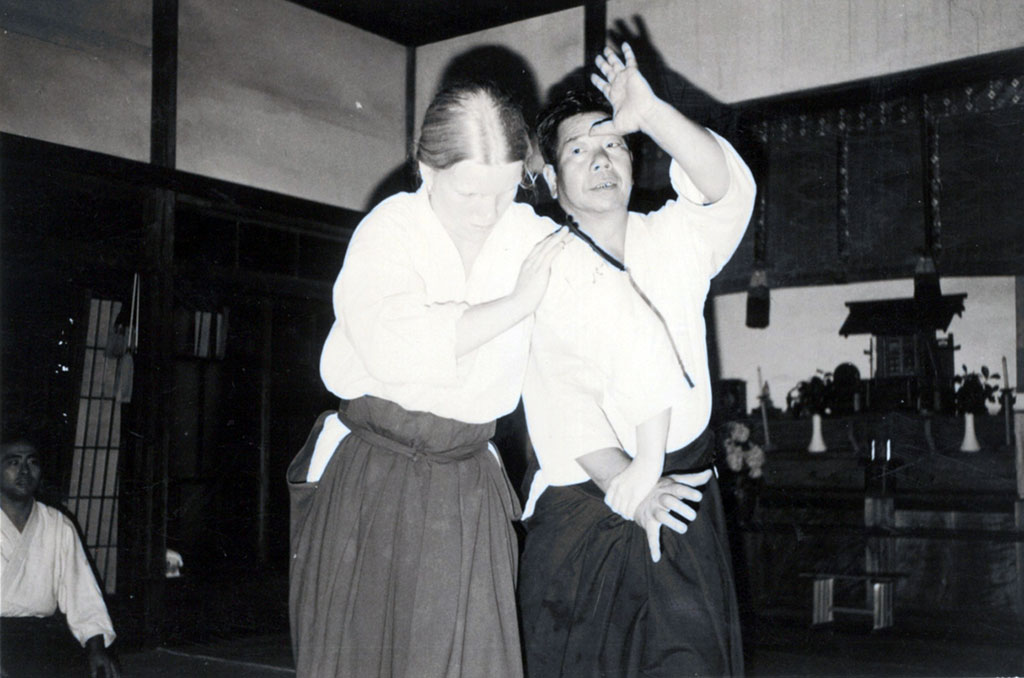

Patricia Hendricks taking ukemi for Saito Morihiro Sensei in Iwama

Patricia Hendricks taking ukemi for Saito Morihiro Sensei in Iwama

I remember one time in Iwama—the countryside—where the grass was growing tall, and he mentioned that it needed cutting. I offered to do it, and he said, "Oh no, no, no, women can’t do that." I thought, "You just threw me across the room, and yet I can’t cut grass?" That moment stood out to me. Around that time, Daniel Russell was a soto-deshi. He had learned Japanese in six months and was already moving into a political career. He later went on to work at the United Nations and eventually served as director of the Security Council under Obama. He was a close friend of mine. Daniel had the confidence to challenge things. He told me, "Look, I'll teach you how to use the machine, and if you want to do this—if you want to challenge Saito Sensei a little—go ahead. I’m right behind you." So he set me up, and later, I realized that’s just the kind of person he was—that kind of confidence took him far. So, I went out at 6 AM and worked for six hours, cutting all the grass. Later, I saw Saito Sensei go into the dining area. I thought, "Oh no, he's going to be really mad that I did this without his permission." But this moment defined why I stayed his student for so long. He came out and said, "Pat, thank you so much for cutting all the fields. I know it was a long workday for you. I made sopa for you—please come in and have lunch." I was stunned. I couldn't believe he did that.

After that, he started to change. Over the years, he began accepting female students, understanding their capabilities. He was an old-fashioned guy, but truly unique. You probably know, he spent 23 years as uchi deshi with O Sensei. That was the start of it. Later, I went back and helped Bruce host him—that was in the ‘70s. As time went on, I got more and more serious. After graduating from UC Berkeley, I went straight into the Japanese Consulate. At that time, I wasn’t sure if I wanted to run a dojo full-time. The General Consul brought me into the economic department. Before long, I was writing diplomatic letters, reading about ten newspapers a day, analyzing Japan-U.S. trade relations. It was an exciting time, with issues like the medfly crisis and trade wars happening. But when I looked at the consuls, they didn’t seem happy or healthy. I spoke to my boss and said, "I think I might take a year off to see if Aikido is really for me." Saito Sensei encouraged me, saying, "You could do this—you’d be one of the first women to have a dojo." He was already using me for major demonstrations, books, and videos.

Patricia Hendricks taking ukemi for Saito Morihiro Sensei at the Nippon budokan in May 1994.

I took a chance. I found a dojo space in San Leandro, California. It had previously been a Taekwondo school, but the owner had been evicted. I negotiated with the landlord, and he said, "Well, since it's a sheriff’s eviction, you can stay. I won’t charge you rent for six months, but there won’t be lights or water." So, I went for it. The place already had walls, carpet, and mirrors. My students helped me build it up. We trained in the mornings without lights, and at night, we used lanterns. Before I knew it, six months had passed, and the landlord only charged me $800 a month—a great deal for such a big space. I stayed there. The landlord’s mother, an old-fashioned Italian woman, treated me like family. I would visit her to pay rent, and she would say, "Honey, I know you're young and trying to start a business. I got you a bag of groceries because you don’t look like you have much money. Also, I made you lunch." She kept me going. They barely raised the rent over the years. When she passed away, she had told her son, "Take care of that young girl." And he did.

Now, we just celebrated our 40th anniversary, and I’ve been doing Aikido for 50 years. I kept growing my dojo, expanding it, adding rooms for uchi-deshi. We built four rooms, plus a couch and extra sleeping space on the mat for events. Everything felt blessed.

Guillaume Erard: Iwama style is known for its technical precision. In your own teaching, do you approach Aikido beyond just the technique?

Patricia Hendricks: I knew Aikido had a purpose in the world. O Sensei had that vision, and I believed in it too. As I continued, the philosophy and spirituality of it became more important to me.

I kept going back to Iwama, and I had the privilege of training, —like, all the guys would sleep on the mat because there were so many of them. Sometimes there were some rooms, but the old dojo was connected, and it still is, to O Sensei's house. So, Saito Sensei would say, "Okay, all the guys are there, you can't stay in there, so I'm going to put you in O Sensei's house." And so, I slept in his bedroom. You know, he had already passed away. Sometimes I slept in his wife's room, you know, depending on what was going on. It was such a beautiful energy in there, and I also felt like I had lots of dreams about O Sensei and other things.

O Sensei's room in Iwama

So, I felt like, from that time, there was something I could do for the world. I didn’t know exactly what it was, but now it's more clear to me. And, you know, I felt that even though our style—Iwama style—is pretty physical, with a lot of weapons and a lot of things like that, within that, I felt there was the spirit of O Sensei and Aikido. And that, Saito Sensei also had that spirit, but he just didn’t talk about it so much. His son Hitohiro did. His son and I were about the same age, and we sort of grew up together from the time we were teenagers.

Guillaume Erard: It is my understanding that Saito Hitohira Sensei is quite religious in his daily life.

Patricia Hendricks: Very much so.

Guillaume Erard: Wasn't it the case for his father?

Patricia Hendricks: He wasn’t as interested, but then, in the middle of everything, he’d be in the field, we’d be doing weapons, and he would just—sometimes he would just go off and chop wood and come back. And he would take his jo and do that thing that O Sensei did, just connecting.

Ueshiba Morihei training in the Iwama Dojo in 1962

And then, a lot of times, he would just do different things. He would say, "Let’s do Aikido blindfolded. Let’s do Aikido in a way that we can go from basic to movement to advanced techniques."

Hitohiro was going to this psychic in the Iwama town. He was going to her and just asking her about some things, and she said, "Oh, I see that your father has this old man with a beard sitting next to him all the time." And so Hitohiro said, "Oh, that's my dad’s teacher. That’s O Sensei." And then, a few other things would happen like that.

And then, sometimes when Saito Sensei would come to teach, like seminars, and we were just together, then he would say some things. You know, Saito Sensei would, but not as much as Hitohiro, for sure. At that time, his name was Hitohiro, and it’s hard for me to say "Hitohira" because I grew up with him. And so, he and I, we would just talk about things together and talk about spirituality. One time, he had a Japanese reporter come and ask him about kotodama, and then I just stayed with him and translated the kotodama meanings. That was, like, really easy for me because we would talk about it all the time.

Guillaume Erard: What we know of Saito Sensei through the videos is that very formal, static way of performing techniques. And I suspect that’s a didactic sort of approach. Were there also more dynamic classes?

Patricia Hendricks: Yes. Yes, there were. There were so many. And a lot of times when he came to California, he was just doing technique after technique. But in his later days, I remember one of the last demos—it was the All Ibaraki—and then he looked like O Sensei. He was doing all kinds of things with me and Nemoto Sensei. He would say to us, "Let’s do blindfolded today. Let’s try this." He even said, "You know, in America and in the foreign countries, you can be really creative, and nobody thinks you’re odd. But in Japan, it’s hard to do that." But he said, "I have foreign students, so I can do that."

He was always experimenting with different things. And I saw that about him. So I knew the didactic approach was there too—because maybe somebody comes in, and they’ve never done Iwama-style, so he has to do that. But then, when someone has been there for a long time, he starts pushing them to Takemusu. Yeah, he wasn’t just about technique at all.

He talked about O Sensei being next to him, you know, in another dimension. He would talk about different things. One time, I was doing tarot cards, and I said to him, "Do you want me to do tarot? Because I did it with Hitohiro." Hitohiro he was right there with me. I actually helped answer his question about whether he should focus on opening a restaurant or do Aikido. And the tarot cards told him yes. But then Saito Sensei just went "ato-de"—you know, that thing, "later" And it became a joke with Hitohiro and me. Anytime Saito Sensei would go "ato-de" it meant "Nope, not happening." It was always kind of like that (laughs).

But he was amazing that way. People saw him as strict, and he was very disciplined, but he was also big-hearted. He was amazing like that. Hle is like that too. And Okusan—jeez—she was the toughest woman I ever knew. But in a really good way. And I would always say to Saito Sensei, "Why don’t you bring your wife with you?" And he finally did. He finally did.

Saito Sensei and his wife, Sata in Iwama

Guillaume Erard: Have you been to Iwama since you arrived in Japan this month?

Patricia Hendricks: Yes I did. First, we went to Hitohiro Sensei's house, he was so glad to see everyone. And then we went over to see Inagaki Sensei. After that, we walked up to Atago-san, saw the jinja, and it was a beautiful day.

Guillaume Erard: Did Saito Sensei explain where O Sensei's weapons practice came from? By extension, do you know where the kata that Saito Sensei created come from?

Patricia Hendricks: According to Saito Sensei, O Sensei did try different arts out, like Iaido and some kind of Kenjutsu and Kendo, not to any big extent. But from all those things that he did, he was able to create at least Aiki-jujutsu. And then, when the war ended, he started changing his techniques to what we now know as Aikido.

I would hear all these stories where Saito Sensei said they were farming. They were actually not having much money at all, so they had to do rice and vegetables and sell them. They would be out working in the fields, and all of a sudden, O Sensei would say, “Oh, Saito-kun, bring this bokken,” and then he would start to do movements that eventually became the kumitachi, and then movements even with the kentai-jo, even though that wasn’t formulated until later. And then the jo and jo, which became kumi-jo.

Saito Sensei performing the 31 jo kata

So he did those movements, but he only formulated the 31-kata and the kumi-tachi, and then a little bit of the 13-kata. And he said to Saito Sensei, “All these things that we’ve been doing, you take them and you formulate them before I pass away. Why don’t you do that?” So that’s why he did that. And the last thing that he did, he did kumi-tachi all the way to the kimusubi. He did the 10 kumi-jo. Not right away—he did 1 through 3 in the late ’70s, and then a little bit in the early ’80s. He would come to California and say, “Oh, I’ve done 4 and 5 of the Kumi-Jo,” and then later, he did 6 and 7, and then 8, 9, and 10.

So by the time it was 1988, a lot had happened. In ’88, myself, Louis Jumonville—who is my top student—, he and I and Hitohiro Sensei and Teruo, a Japanese guy that we all got close with, we were in the morning class—like four people in the morning class. Sometimes it would be bigger. But what happened was, because Hitohiro Sensei and I were there, he was just bringing everything out. He said, “Okay, next we do this. Next we do that.” And then he went like this, he went, “Well, now what do I do? We’ve done everything.”

Then he said to Stan Pranin, “I think I’m going to do a little bit of a separate weapon certification, so people know that’s the thing.” And he said, “You know, I never formulated the kentai-jo. O Sensei told me to do that later.” He said, “That’s what we’ll do.” So he took months and months and did all that. He went all the way to 7, and he said to us—Hitohiro Sensei and I—“If I pass away before I get to 8, 9, and 10, you guys do that.”

And I waited for Hitohiro Sensei, because he’s my sempai, but for some reason, he didn’t want to do it. And I said, “Well, if you’re okay, I’m going to do that.” So I formulated 8, 9, and 10. And Hitohiro Sensei has been the most support that I could ever ask for, and he’s still my Senpai, he’s still the person that I look to. And I hope that he continues for years and years, because he is a big role model for me.

So what exists from Saito Sensei is the 5 kumi-tachi and ki-musubi the 10 kumi-jo, the 7 kentai-jo, then the 13 kumi-awase, jo and jo, and the 31 kumi-awase. Now, what I’ve done is, I’ve taken the 13 jo and jo and made it into a kentai-jo kumi-awase, and I did the same for the 31. You want to keep growing, you know? So I felt like I got the permission from both Saito Sensei and Hitohiro Sensei.

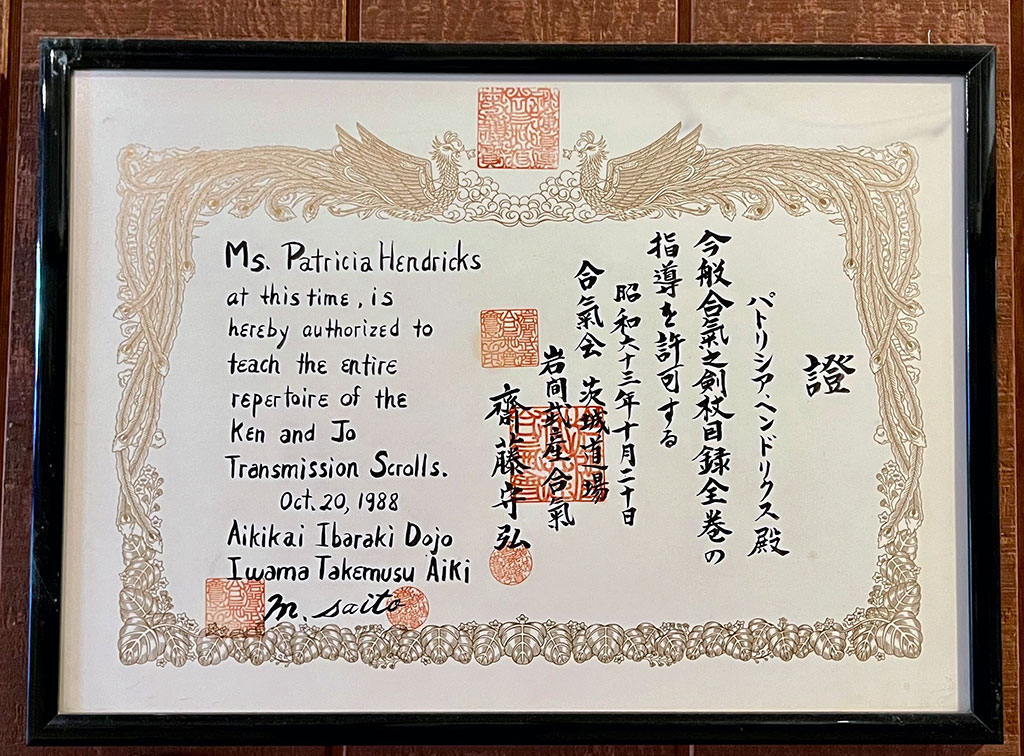

And then Saito Sensei started doing all the weapons certifications. And what he did was, he gave me something like a menkyo kaiden. He said, “You know, I have nothing more to give you,” which isn’t true, but he said, “I have this to give you, and it includes anything that I even will do in the future.” He wasn’t passing away yet. So then that became a thing. And he acknowledged to me and, of course, his son, to do the weapon certification.

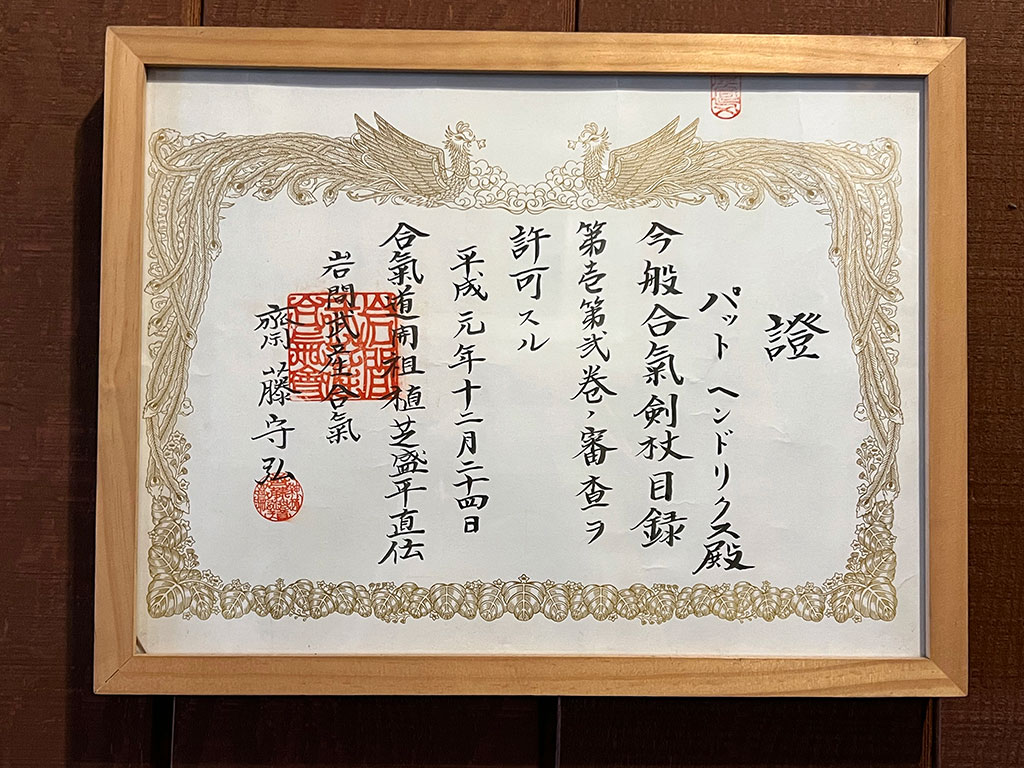

Certficate stating that Patricia Hendricks is entitled to direct examinations for the first and second scrolls of Aiki sword and staff. Issued in Iwama Takemusu Aiki on December 24, 1989, and signed by Saito Morihiro.

Certficate stating that Patricia Hendricks is entitled to direct examinations for the first and second scrolls of Aiki sword and staff. Issued in Iwama Takemusu Aiki on December 24, 1989, and signed by Saito Morihiro.

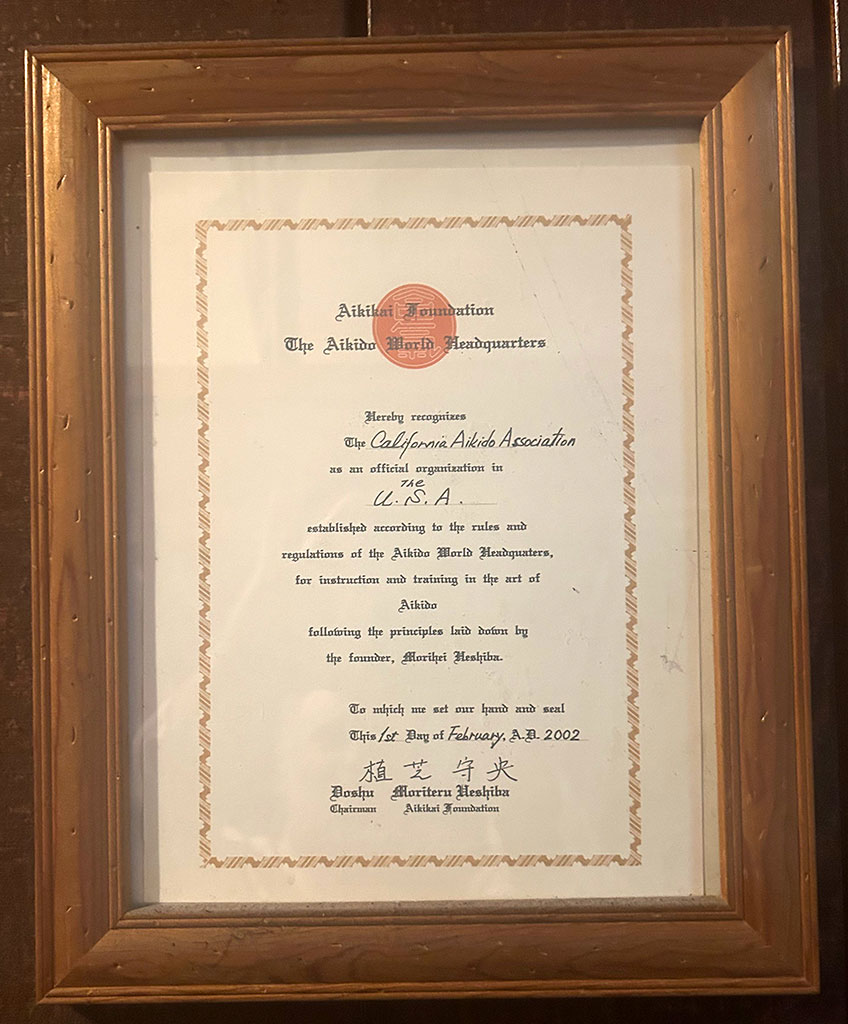

I did a different kind of certificate, which Hitohiro Sensei was like, “Yeah, you should do that, you do that.” And he did his own for the Iwama-ryu, but we actually got permission from Doshu. The secretary of the California Aikido Association (CAA) said, “Well, you know, Pat is wanting to do the certificates for her students, and she’ll always do the Aikikai, always", I won’t go away from the Aikikai. So Doshu said yes. It was the first time that he agreed on that.

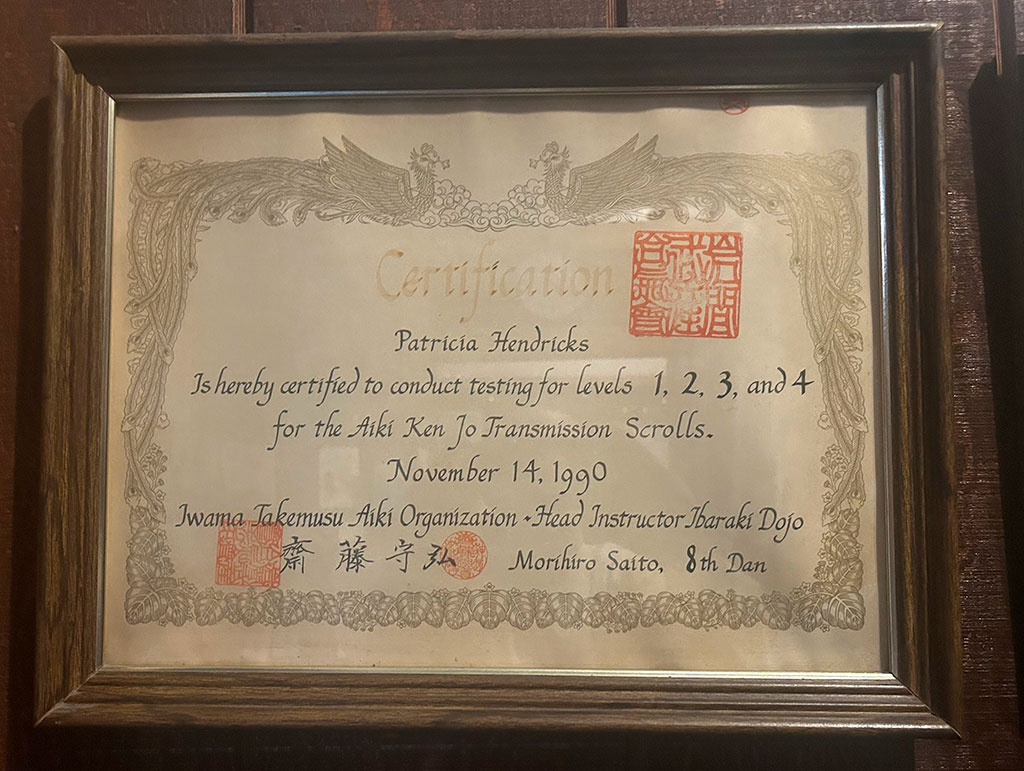

Certificate stating that Patricia Hendricks is entitled to direct examinations for the first to fourth scrolls of Aiki sword and staff. Issued in Iwama Takemusu Aiki on November 14, 1990, and signed by Saito Morihiro

Certificate stating that Patricia Hendricks is entitled to direct examinations for the first to fourth scrolls of Aiki sword and staff. Issued in Iwama Takemusu Aiki on November 14, 1990, and signed by Saito Morihiro

Guillaume Erard: Does that "menkyo kaiden" you speak of specifically refer to weapons, or does it include everything, including taijutsu?

Patricia Hendricks: Everything.

Guillaume Erard: The five mokuroku that Saito Sensei delivered are for weapons only, right?

Patricia Hendricks: But he didn’t say—I have one that says "five", then I have the one that says "All of Aikido menkyo kaiden", then I have the one that says "Any weapons, past, present, or future, will be there for you". And it was strange, because he said to write it in English so that people could read it. He wanted that. So he wrote in English, and he said, “I hereby say that whatever will even be in the future, at any time, you have nothing more—I have nothing more to give you.” You’re on your own, in a way. And I forget exactly the wording, but he asked me to put it in English, and then he took his pen and put that over the English like that, so it looked like calligraphy.

Certificate stating that Patricia Hendricks is granted the permission to teach the complete catalog of Aiki sword and staff. Signed by Saito Morihiro on October 20, 1988.

Certificate stating that Patricia Hendricks is granted the permission to teach the complete catalog of Aiki sword and staff. Signed by Saito Morihiro on October 20, 1988.

And so I have those three. But I have this other one that says, “You are the only one that can teach the weapons formally, and you are the only one that can give the certificates out.” So I was cautious to do that, because Hitohiro Sensei was doing it, and I didn’t want to do something that only he should do, you know? So I held back a little bit. But now, he knows that I do that, and he’s so happy about it.

Guillaume Erard: My understanding is that the parallel certification that was happening in Iwama was causing some friction with the Aikikai.

Patricia Hendricks: Yes, because he went out of the Aikikai.

Guillaume Erard: I mean, I don’t know whether I have my facts straight, but one of the reasons why Hitohira Sensei broke away from the Aikikai is because he wasn’t ready to let go of that particular certification system in Iwama. If that assumption is correct, you seem to be in a particular place—being able to both represent the Aikikai and be able to do award weapons certifications by yourself.

Patricia Hendricks: Yes. Saito Sensei and Nidai Doshu at the time, they went way, way back—as you know—kind of like buddies. They were close. But then things happened with the dojo, and they were going to sell it. Little by little, things got better, but no one expected Saito Sensei to pass away that early. And then he did.

After that, Hitohiro Sensei decided to go a different direction. For me, he knew I would be with the CAA, which meant I was with the Aikikai, and he totally supported me on that. When I got my seventh dan, I was a little nervous to tell him. But he already knew, and he said it first. He told me, "I just want to let you know that I'm so proud of you for getting your seventh dan." And I told him, "well, that’s just the system I’m in with CAA, and that I’m also loyal to Saito Sensei". He understood. I think he’s happy where he is now, and he has a really wonderful group.

Patricia Hendricks receiving the 7th dan in Aikido from Sandai Doshu Ueshiba Moriteru in January 2012.

Patricia Hendricks receiving the 7th dan in Aikido from Sandai Doshu Ueshiba Moriteru in January 2012.

Guillaume Erard: So there was no expectation from Hitohira Sensei's perspective that you would follow him when he went on his own?

Patricia Hendricks: Not at all. He said to me, "I know that you will always bring forth the teachings, the weapons, and the taijutsu." And at the same time, Sandai Doshu would say to me, "You do the Aikido that you do," and he never criticized me. Both Sandai Doshu and Hitohiro Sensei supported me completely. And they also knew—like in Sandai Doshu’s case—that I have many, many Aikikai friends. It’s very natural for me.

Guillaume Erard: Did the freedom that you currently enjoy, notably awarding your own certificates, come from the legitimacy that you got from the certficates that you got from Saito Sensei, or is it something else?

Patricia Hendricks: When I came back to Iwama and I was a sandan or a yondan, and I still thought, "Well, I have to do exactly what they’re doing." But both Saito Sensei and Hitohiro Sensei would say to me, "You know the basics. Now you have to start doing Takemusu. Now you create your own things." They gave me that freedom. And I also felt that freedom with Sandan Doshu, that he was fine with the kind of Aikido I do, but I’ve grown in different ways. I love to move, so a lot of my Aikido is very movement-oriented. It’s a mixture of things.

Certificate of recognition of the California Aikido Association (CAA) by the Aikido Wolrd Headquarters signed by Ueshiba Moriteru Doshu on February 1, 2002.

Certificate of recognition of the California Aikido Association (CAA) by the Aikido Wolrd Headquarters signed by Ueshiba Moriteru Doshu on February 1, 2002.

Guillaume Erard: Stanley was very knowledgeable about Ueshiba Morihei's history, but he told me that he was not very interested in the technical aspects of Daito-ryu. Did you and Stan talk much about Daito-ryu? Do you have any interest in it?

Patricia Hendricks: Yeah, well, Kondo Sensei came in, and that was a big thing because he was doing the Aiki Expos, and we were there. I was one of the teachers, and I would go to the classes all the time. Actually, through the years, I had a lot of friends in Taekwondo, Karate, Naginata, Kendo. I did some Iaido from one of Chiba Sensei’s students. We would teach each other. He would show me iaido, and I would show him the jo from Saito Sensei. Same thing with Bruce Bookman and Rick Stickles.

But I mainly did Aikido—I never stopped doing Aikido to do something else. But Daito-ryu I found it interesting and I know it’s historical, but I don’t know the real truth. I don’t know how much O Sensei really did in Daito-ryu. I know Stan’s the historian, but I’m not sure how much information he could have. Maybe it’s written somewhere.

Guillaume Erard: Well, Stan didn’t have much technical knowledge in Daito-ryu, but he knew the history well. On my part, I’ve also been researching this, but I did spend time learning the technical repertoire in Daito-ryu, and I’ve been able to match the curriculi. It is clear that what O Sensei did the end of his life maps really well to Daito-ryu. In my opinion, he did and taught Daito-ryu all his life.

So going back to the notion of weapons. In the Daito-ryu curriculum of most schools, taijutsu comes, way before the ken. Ken is not usually considered a core part of the practice, at least not at low and intermediate levels. What I am going to say isn’t very politically correct, but most Daito-ryu people aren’t good at weapons. It therefore seems consistent with the fact that O Sensei did not teach weapons very much at all, just like his own teacher, Takeda Sokaku. On the other hand, in Saito Sensei’s school, you have this triptic of tajutsu, jo and ken, with pretty much equal time allocated to each. This is very unusual in Aiki arts.

My question is therefore—why are weapons so important in Iwama pedagogy? What relationship do you see between the weapons and the taijutsu? How does one inform the other, either historically, or in your practice?

Patricia Hendricks: For me, I just grew up with weapons. I do weapons every single day. It’s like a part of my body. There’s a spirituality to it. The forms I got from Saito Sensei, which came from O Sensei, they flow through my body. I don’t think about it much. I just know that when I do weapons, I can bring that into my taijutsu. And then the taijutsu—that’s the iai—it goes with the weapons. It’s a very real, palpable thing for me. I don’t try to figure it out. I just take things in naturally, and I let them express themselves. Sometimes, I don’t even know how they’re going to express themselves. That’s just my path right now. I don't have a specific answer for that, but for me, that really works.

Guillaume Erard: If I could rephrase that question—when building up physical qualities, could you use a different system of weapons than that of Saito Sensei, or do you think it’s the act of manipulating a tool that connects the body together?

Patricia Hendricks: For me, the weapon becomes alive. The spirit of the weapon is there. I actually do a lot of live weapons—machete, live sword, live knife. The machete, for example—I don’t know why, but it just feels really comfortable for me.

For the World Games, Doshu asked me to be the representative, and Kei Izawa wanted me to do a very martial demo so that Aikido wouldn’t get kicked out from the World Games. They wanted the World Games to see that it was martial, so I said, "Okay, I’ll use live weapons." But on the last day, Doshu must have told Irie, "You have to talk to her and tell her not to use live weapons." And it was funny because Wilko said, "Well, you’re Japanese, you should tell her." And Irie was like, "No, no, no, you’re foreign, you should tell her." So Wilko came over and explained it to me, and I said, "Okay, we’ll use wooden weapons." It turned out fine.

Patricia Hendricks Sensei demonstrating at the 2022 World Games

Like, we were filming at Josh Gold’s, and you know Dan Inosanto, right? He was watching my demo. His student, Mark Cheng, was there. They were doing a little seminar and about to leave. I said to Josh, "Do you by any chance have a machete?" And he said, "No, but that guy—Mark Cheng—probably does." Then he handed me this never-been-used, sheer steel machete. It was beautiful.

Patricia Hendricks, Mark Cheng and Josh Gold at Ikazuchi Dojo

And my student, Louis, he’s always protective of me, and he was like, "We are not using the machete. It’s too sharp. Somebody’s going to get cut." And I was like, "It’s okay." And I didn’t cut anybody, and it didn’t cut me either. But I slept with it. I put it in front of the altar that I bring when I travel. It was new—no one had ever used it before. I just let the energy transfer. And by morning, it had the spirit. That’s how I see weapons. They’re alive. They teach me, and I teach them.

I have a sword that Saito Sensei made from scratch, and Hitohiro Sensei has given me a lot of weapons. I feel their spirit in them, too. Years ago, I decided—I don’t want to figure things out. I just want to see what comes through me. And it does. Saito Sensei was always happy with that. It's hard to explain. Some of my students want to figure it out with their head and I'm like "Don't do that, you have to let your body give you the wisdom". I call it body wisdom.

Guillaume Erard: The reason I am asking this is that when we see O Sensei, he practiced and taught in a way that suggests that he was not particularly attached to one weapons system in particular. He taught some forms to Saito Sensei, and something completely different to Hikitsuchi Sensei. If his taijutsu came from weapons, one might have expected something more consistent or integrated.

Patricia Hendricks: Yes.

Guillaume Erard: But I get it, that if like you, one has that sort of holistic approach, then there's really no explanation to give. It’s only when one becomes very idiosyncratic with one's weapon system that one actually has a lot more to explain, technically and historically.

Patricia Hendricks: That's right. That's right. And I mean, I still do technical things, of course, because I have to test them. In my group, there are a lot of advanced people now—some are up to rokudan and shihan—so they have to know the weapons. I have to give them the certificates, but they're very diligent, and they're like me in the sense that they are very body-oriented. So it seems to work. It really seems to work. You know, there are some people who are still in their heads, and I have to try to drop that into their bodies. But they're getting better. Most of the people who have been with me for a long time are already like that.

Guillaume Erard: We get this sort of view. Saddly, Iwama-ryu in France suffers from the very negative image that some of its high ranking teachers who seem to go out of their ways to be derogatory of other styles, while remaining extremely idiosyncratic and providing very little evidence to back up their claims. You, on the other hand, really surprise me with how open-minded you are. But I guess that people who don’t train so deeply tend to be more attached to the form, because it’s just the snapshot they have seen, and they replicate whatever that is that they saw.

Patricia Hendricks: That’s exactly it. That’s exactly it. But for me, I just wanted to add this: A lot of times, I’ll go into that state that O Sensei talked about, where there’s no time and space, and that’s when things happen for me. That is the next level.

No matter what, Saito Sensei and Hitohiro and… oh my gosh, his wife—his wife one time—there was a big radio thing that was going to happen, and Saito Sensei just couldn’t be there. And so he said, "Pat, you can do it." And I was like, "Oh my God!" So Okusan said, "I’m going to come, and I’ll be the person just talking about what Iai is all about, and you just do the physical thing." And I remember, because she was so supportive of me, I just put myself into that time and space and then did what Saito Sensei would do. I was trying to do that. And everybody was happy with it. So, you know, I was okay.

Those kinds of things happen every now and again. And I think part of it was that Saito Sensei really was an amazing teacher. He could bring everybody as high as he could. He really could do that. And some people might think he was kind of mean—he could be—but I didn’t see him that way. It was more like he was just trying to push you to the next level.

Guillaume Erard: Thank you very much for your time.

Patricia Hendricks: Thank you.