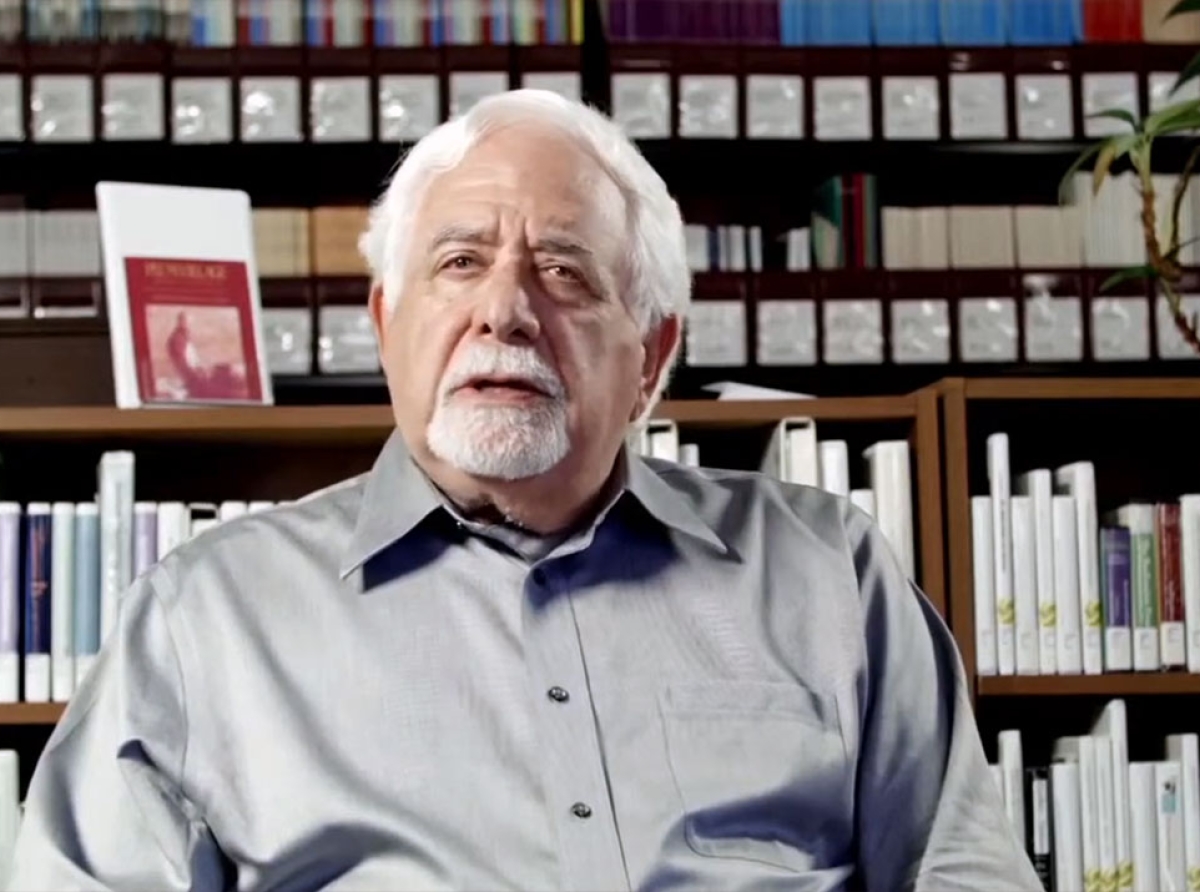

Dr. Robert Frager is a distinguished figure in the aikido world, known both for his direct training with founder Ueshiba Morihei and for his contributions to the fields of psychology and spiritual development. An 8th dan in aikido and the founder of the Institute of Transpersonal Psychology, Dr. Frager brings a rare blend of martial, psychological, and spiritual insight to his teaching. In this interview, he shares reflections on his time with O Sensei, and the art’s deeper relevance beyond the mat.

Guillaume Erard: As you may know I have a keen interest in the pioneers that went to Japan years ago and got the chance to practice with O Sensei. Now of course, I didn't get the chance to meet O Sensei myself, so my way to compensate for that is to gather the stories of the people who did. I have been the student of Alan Ruddock, Henry Kono, and I did meet Ken Cottier as well, although I didn't know him personally. I've prompted those people to tell me their stories, and of course, your name and that of a few others came up many times. Then last January during the Kagami Biraki, I was present at Hombu Dojo, and when they unveiled the names of the promotees, I saw that your name was listed as an 8th dan. And I thought to myself, "Oh yeah, that's true, I still have work to do in recording those stories." I guess where I'd like to start is how you started martial arts.

Robert Frager: I started with judo as a freshman in college. I went to a small college, Reed College (Portland, Oregon), and everyone had to take some kind of physical education class. There was a judo class being offered and I thought, well, that was a lot more interesting than basketball or baseball, or the usual stuff, so I began practicing judo.

We had a first kyu brown belt as our teacher and we practiced in a sort of loft, and I was always afraid that if you threw anybody high their feet would hit the ceiling, the way O Sensei did with TenryuTenryu Saburo (天竜 三郎) was a professional sumo wrestler. He discovered Ueshiba Morihei's aikibudo in Manchuria in 1939 and became his student.. I loved it.

My home was in Los Angeles, and when I went home for the summer, I spent the summer training with a wonderful judo teacher named Hal Sharp. Hal trained at the Kodokan. In fact, he was the co-captain of the gaijin squad, or whatever they called it. He was a very sweet, very wonderful guy. I really enjoyed training. It was a small dojo in the San Fernando Valley in Los Angeles. We became friends, and Hal planted the seed. Because I was sincere and showed up a lot, he said, "Bob, you know, you might think about going to Japan." Which I had never done. And he said, "You know, my old teachers are still alive, and if I wrote to them, I'm sure they'd be happy to put you up." I thought, "Wow, what an incredible opportunity." And I started thinking about it, and that thought just stayed with me for the next few years. I would train with Hal in the summers and train at college, although I think the judo class stopped after another year because the teacher graduated.

And then I also started karate with Ed Parker, who was one of the very first karate teachers in the United States. And because I was again only there for the summer, Ed and I arranged for me to have private lessons with him. So I would drive to Pasadena, which is where his main dojo was, and we'd train, and that was another wonderful door that opened for me. So I sort of knew how to throw a punch and take ukemi. At least I threw a punch in the style of Kenpo Karate, which was stronger than it was fast in many ways. And then I kept thinking, "Gee, I'd love to go to Japan. I could train." You know, I had read "Zen in the Art of Archery" and thought, "Well, what a wonderful way to get to know a culture."

I started applying for fellowships, and I never got one because I didn't have a good enough reason. I couldn't articulate this sort of mystical notion of getting to know the soul of Japan through sweating. I finally did, at the end of my second year in graduate school, receive this big package. It was sort of the last day of the school year, and I looked at it. It was from the East-West Center in Hawaii, and my first thought was, "Damn, they must have accepted me because this is too big and substantial to be a rejection letter." And it said, "Yeah, Bob, if you would like, you can come for two years, all expenses paid fellowship." I negotiated for more time in Japan because their normal fellowship was a year and a half in Hawaii and six months in Japan or China or whatever Asian country one wanted to go to. I thought, "Well, I may have blown that, but I really do want more time." In th eend, I got the longer stay.

While I was in Hawaii, I was friendly with another student who was a karate student, and we talked about the martial arts. One day he came up to me with this book, lovely illustrated large-sized book. "This is Aikido" by Tohei Koichi Sensei. I still remember opening it to O Sensei's picture, and I sort of was just struck by the power of his presence, if you will. And I read the section of the book called "Memoir of the Master", and I loved the relatively short poem. I was so taken with the book, and something in me said, "I've got to do this." I don't know what it was. It wasn't particularly logical.

I had heard of aikido before and even seen a demonstration in the US, which I didn't think much of. This was early days, maybe 1960, 1961. They did multiple attack, but they were all holding back, and I found it embarrassing in a way. The demonstration was done by Takahashi IsaoTakahashi Isao (高橋一佐男, 1912 - 1972) was a high-ranking kendōka who was among the first Hawaiians who started aikidō under Tohei Koichi in 1953. He relocated to Los Angeles in 1960 and headed the Los Angeles Aikikai, and then the Illinois Aikido Club., who was the man who introduced aikido to the mainland. And he was fairly competent, but again, it was sort of Ki Society. Well, it was pre-Ki Society. It was Tohei teaching the Americans. And he was an older man. His art was really sword; he was a great kendoka.

So I saw the book and I said, "I have to train". And it turns out the hombu dojo of Hawaii, was a 15-minute drive from campus. So I started training a couple of times a week in the beginner's class, and I really loved aikido and loved Tohei Sensei.

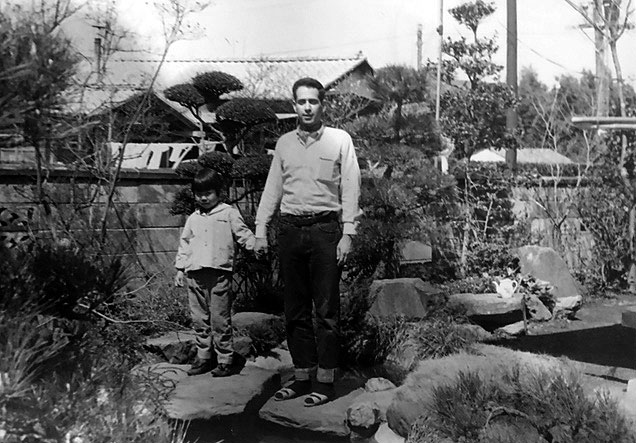

Then when I got to Japan, on the first day, I took the bus and found myself in Wakamatsu-cho, and it was the old dojo, which I still miss. It was a beautiful traditional Japanese wooden building. Before I left, Yamamoto SenseiYamamoto Yukiso (1904 - 1995) was a former jūdō champion who was among the first people who started aikidō in Hawaii under Tohei Koichi in 1953. He became the Chief instructor for the state of Hawaii in 1959 and was the Chief instructor at the Honolulu Aiki Kwai after its construction in 1961., who was the chief instructor in Hawaii, and who was a great judo sensei before he met O Sensei, wrote me this beautiful letter of introduction. He sat me down in his little office, and he pulled out a really nice sheet of rice paper, made ink, and started brushing a fancy letter of introduction. And he told me to train well because I was representing Hawaii. I was an American, so I didn't understand that part of Japanese culture particularly.

So I went in and I handed my letter, and it was a one-man office in those days. This nice older man disappeared. He said, "Thank you", and disappeared, and I was in the entrance wondering what to do. It seemed like forever, and he brought me to the room next to his, which was the room that Doshu and O Sensei would sit in. I had finished two years of university conversational Japanese and two years of reading and writing, but I just felt like a schoolboy who stuttered. "I'm so honored, Sensei. I have no words". I didn't say "I have no words", but clearly I did. So I'm sitting right in this small room with O Sensei and Kisshomaru Sensei. It was sort of uneasy on both sides, and there were very few foreigners around, so it sort of was a big deal, as you could see from those newspaper articles you have managed to take out of nowhere.

Kisshomaru Sensei said, "Did you bring your dogi?" and I said "Yes", and he took me out to the three o'clock afternoon class and paired me up with an American who'd been living in Japan. And that was the beginning of my real aikido career. I jokingly say that I learned just enough in Hawaii to get in trouble.

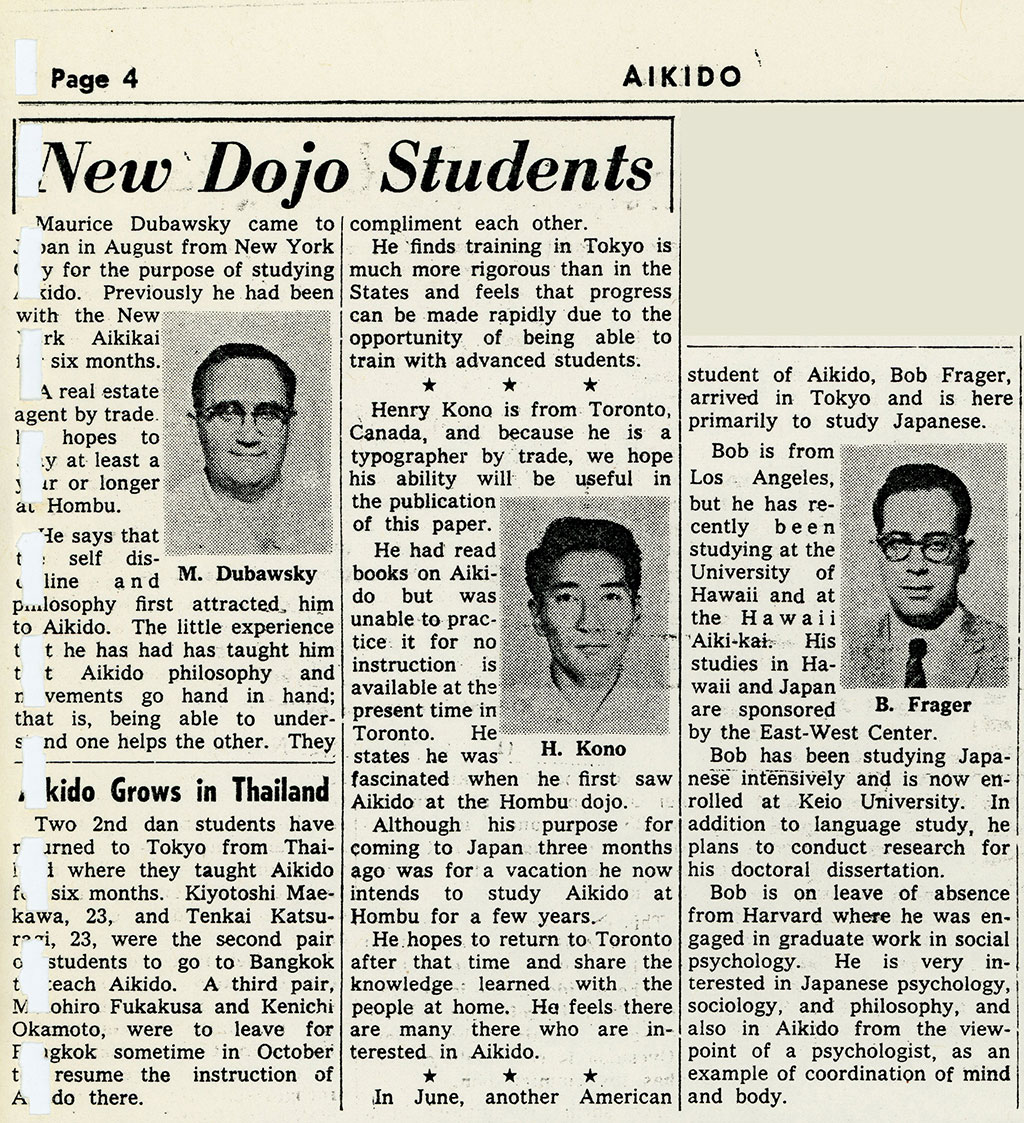

Guillaume Erard: Talking about the foreigners who were there at the time and about that aikido newspaper in English—there's an article that states that you just arrived at the same time as Henry Kono. Can you remember who was there at the time, except you two?

Article from the October 1964 issue of the Aikido Newspaper mentioning he arrival of Henry Kono and Bob Frager.

Article from the October 1964 issue of the Aikido Newspaper mentioning he arrival of Henry Kono and Bob Frager.

Robert Frager: Well, it all merges. I trained every day, seven days a week. Robert Nadeau was there; in fact, he was the first one I trained with. Terry Dobson was living in Tokyo, but I didn't meet him for months. He was running around trying to import posters or something. Henry Kono was there. Henry, Alan Ruddock, and I became friendly, and so was Ken Cottier. Virginia Mayhew came nine months later, I think. And she was sort of the mother of the group. We were all these younger guys.

Robert Frager, Alan Ruddock and Henry Kono. Aikikai Hombu Dojo (c. 1966)

Robert Frager, Alan Ruddock and Henry Kono. Aikikai Hombu Dojo (c. 1966)

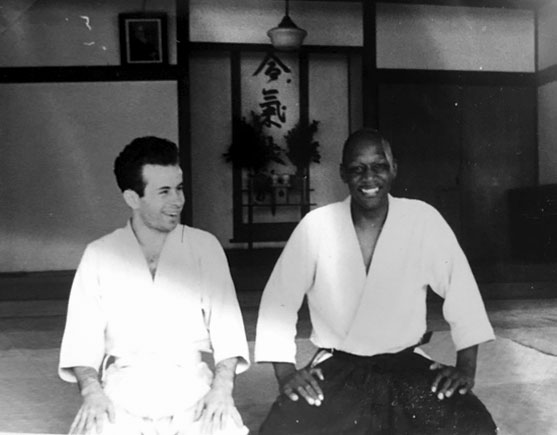

There was a guy named Robert Days who was African-American, the only one who ever trained at Hombu in those early years. Strong, he was very good. There was a guy named Joe Deischer who every once in a while, you see his picture. People usually don't identify him because they don't know him. But I knew Joe. Joe actually had gone to Reed College; I knew him from college. And he was a student of a Japanese tai chi teacher, believe it or not, and that was what he focused on, although he also trained at Hombu. And he had returned to the States, and years later when I started my own school, I had him teach tai chi, so we stayed in touch.

Joe Deischer and Robert Days in the old dojo

Joe Deischer and Robert Days in the old dojo

There was a Swiss man who... I think there was Gerd WischnewskiGerd Wischnewski (b. 1930) is a German Aikidō practitioner who was among the first generation of aikidō teachers in Germany from 1965. He trained in Japan in the 1960s under prominent masters—including aikidō founder Morihei Ueshiba. He held black belts in Aikidō, Jūdō, Kendō, and Karate. He authored the first German-language Aikidō manual in 1969. Wischnewski retired in the early 1970s due to health reasons., you can probably look up those name.

Henry Kono, Gerd Wischnewski, and a Japanese man.

There was Joanne Shimamoto. George Willard came later, about a year later. And if you mention names, I'm sure I would remember them. At one point, I got a beautiful farewell card. I went back for the summer; I went home because my scholarship allowed me to do that. And you know, it's a big deal when you leave Japan, so a lot of them came to see me off to the Matson Line steamer, and we were all very close. There were about a dozen foreigners.

Guillaume Erard: Can you tell me more about Wischnewski?

Robert Frager: Gerd did not go to Hombu every day, so he was less a part of our little Hombu gaijin group, but I always enjoyed training with him. I think he did kendo, maybe judo as well.

Gerd Wischnewski with Ueshiba Morihei

What happened is I created an aikido archive built on Henry's wonderful photographs, which we archived as part of the library of my school. And it all fell apart, and it's sort of there, but it's not easy to access anymore. And I sort of took some of my best pictures to be scanned as well, my little collection. And what I'm left with is a lovely album with half the pictures gone, and some of them I have in a bag.

Guillaume Erard: Alan did a lot of digitizing when he wrote his book, so it would be nice if one day we could get all those pictures from those times back together because, as you said, there are some people whose names come up quite frequently, but others are in pictures, and we're not quite sure who they may be.

Robert Frager: Well, I started to try to do it systematically. In fact, I sat down with John Stevens, who has lots of pictures himself, and we started going through pictures and talking about, "Well, who was that, and when was that?" And after an hour, it felt like we went through only half a dozen. It was a very slow process. And I haven't really seen John for years now. His health hasn't been good, as you probably know, and he used to come out here. There are some of the teachers here who love to have him teach at their dojos, but he doesn't get around the way he used to.

O Sensei surrounded by the group of foreign students. From left to right: Alan Ruddock, Henry Kono, Per Winter, Joanne Willard, Joe Deisher, O Sensei, Joanne Shimamoto, Kenneth Cottier, a visitor from the USA, Norman Miles and Terry Dobson (photo taken by Georges Willard with Henry Kono’s camera).

Guillaume Erard: I've had particular interest in that English version of the Aikido Shinbun. At least one of your articles was published in there, and I know that Henry served as the deputy editor for some time. Do you have any particular information on that newspaper, how it came about, where the idea came from to get it made in English, and also perhaps how it stopped? Because nowadays all the publications are in Japanese.

Robert Frager: Well, I believe it was started by Bob Nadeau. He was living close to the dojo, and he was sort of a soto deshi and trained hard. He was pretty clear he wanted to be a full-time aikido instructor, which not many people did, not many foreigners. So, you know, he had no Japanese other than "Can I have another scotch or a beer?"

Roy Suenaka, Morihei Ueshiba, Seiichi Sugano, and Robert Nadeau

Roy Suenaka, Morihei Ueshiba, Seiichi Sugano, and Robert Nadeau

In fact, not many of the foreigners could speak Japanese at all. There was Henry, of course, a Japanese-Canadian, and there was me. And there may have been some other Japanese-Americans. My Japanese got really quite good because I was at Keio University. My routine ended up with the 8 o'clock in the morning class, train some afterwards, jump on the Yamanote line, get to Keio, and then take classes, and later add research as well.

And then I became a student of Nakamura TempuNakamura Tempu (中村天風,1876 - 1968) was a very influential martial artist and yogi. He was the first to bring yoga to Japan and he founded his own art, Shinshin-tōitsu-dō (lit. way of mind and body unification., and one week a month, I would attend his lectures at night. So that was a very full schedule. I would often leave the house quarter after seven or something like that, walk to the dojo. I was staying in Ichigaya.

Guillaume Erard: I used to live in Yotsuya, so I know that walk. It's a perfect warm-up indeed. About the newspaper editor, his name was Sid White. Do you remember him?

Robert Frager: I don't remember him, but you know, people would come and often not stay for very long. So we had some people that were in the military who would come down weekends or even sort of commuted to their regular jobs but lived in Tokyo. So I really don't know.

Guillaume Erard: I'm especially interested in how life might have been at the time. I keep asking my seniors, people who were there at the time—I asked Christian Tissier, I asked Didier Boyet, people like this—"Did you take some pictures of how things were?" However, none of them did. And even Henry or Alan, they have all these wonderful pictures of O Sensei and Hombu, but I want to see what life was like and how the urban landscape was, if you could call it that. Anyway, so you were at Keio. Where was the campus at that time?

Robert Frager: There were two campuses. There was one sort of out of town; it was a larger one that was near Tokyo Tower. Actually, when I first moved to Japan, I lived for a while in Nakano. Then I lived for a while in a nice little room in a Japanese temple right near the Mita campus. And then finally, I met Donn DraegerDonald Frederick "Donn" Draeger (April 15, 1922 – October 20, 1982) was an American martial artist and instructor. A prolific author, he wrote several influential works on Asian martial traditions and played a key role in promoting judo internationally, both in the United States and Japan. He also contributed significantly to establishing martial arts as a legitimate field of academic study.. I knew his picture from the back of his books. And there was a famous bookstore, one of the only ones with lots of English books in Ginza. I can't remember the name now. And I met him, I introduced myself, and he was interested because I don't think he'd met any Americans that were training in aikido full-time. So when a room opened up, he offered it to me, and I thought that's perfect because going to aikido rapidly became more important in its own way than going to the university. So I moved into the house with two other judoka and a woman who worked in Tokyo and was never around. One was Canadian, one was British, and they were relatively new to judo, maybe shodan or something like that.

Guillaume Erard: Through Draeger, did you get the chance to practice any of the koryu bujutsu?

Robert Frager: That's what he did mostly, I think. He was fed up with the politics of judo, etc. I mean, for example, I know Hal Sharp came back to the United States, I believe, as a nidan and stayed as a nidan for years and years. And then suddenly, toward the end of his life, there were new people in charge, and it was no longer the old guard in charge, and suddenly they finally promoted him to 8th dan or 9th dan. There was all that political stuff—of course, there's politics everywhere, and I never would have gotten promoted to 8th dan if it wasn't for Bob Cornman, God bless him.

Guillaume Erard: Oh, really?

Robert Frager: Well, he pushed, and he was very good at documenting stuff, and the fact that I really was a student of O Sensei's. Not everybody realized that, but I was. I trained with all the Hombu teachers. My first year, I was really closer to Saito Sensei. Then second year, Osawa Sensei. Then I went back to the States, got my degree, and went back to Japan for postdoc research.

Virginia Mayhew, Henry Kono, Saito Morihiro, unknown, Bob Frager in Iwama

And then after about seven years, I built a dojo up at the UC Santa Cruz campus. It was a wonderful time to be teaching aikido, and I was really into the meditative spiritual part of it. And I did all the crazy things you did when you're young, having people line up and taking ukemi over five or six people, and all that stuff. I threw in Tohei's Ki exercises, Tempu's Ki and mental exercises. So I really had quite a few students, and three of my best students sort of wanted to go to Japan and really study seriously. And they met another Santa Cruz student who sort of dabbled in aikido, and she said, "There's this amazing dojo in Shingu."

You know one thing when I was very much a Hombu monjin門人 (monjin) literally means "gate person" and traditionally refers to a disciple or student who has been formally accepted into a teacher’s school or inner circle of instruction, particularly in the context of classical Japanese arts, such as martial arts, tea ceremony, calligraphy, or Noh theatre., I suppose, for lack of a better name, and when I was, anybody talked about any other teachers from any other dojo, you know how it was?

Guillaume Erard: Yes,it still is that way.

Robert Frager: It was sort of "Hikitsuchi is weird"Hikitsuchi Michio (引土道雄, July 14, 1923 - February 2, 2004). Direct disciple of O Sensei and Chief instructor of the Kumano Juku Dojo, in Shingu, Wakayama Prefecture..

Guillaume Erard: Yes, for sure because his practice was different...

Robert Frager: I mean, he was incredibly good, which I found out later.

Hikitsuchi Michio with O Sensei

Hikitsuchi Michio with O Sensei

This one woman, Karen, introduced my students to Mary Heiny. By the way, I was the one who literally dragged Mary to Hombu Dojo. We were in Keio together. I would come back with these crazy stories about my beloved teacher who did miracles every morning, and so she came and she just went "wow." And a day or so later, she came to class and she had these huge bandages on her shoulders soaked in liniment because she was training and she tried to use strength to make it work, so she strained her shoulder but she never stopped, God bless her. And her Japanese, even way back, was better than mine. She had a great ear.

So she had gone down to Shingu and was really welcomed by Hikitsuchi. She was given the cold shoulder in part because she was a woman and a foreigner. But Hikizuchi was looking, because he knew the real aikido and so he was always looking for people to expand his sphere of influence. And she brought my students down and she became their guide, translated for them, and they fell in love with Hikitsuchi and they stayed there for several months.

And they came back with these stories, they sent me letters and somehow they got all enthusiastic about inviting him. I didn't ask anybody for permission, I mean I was a dojo-cho, and I understand the hierarchical thing, except of course when I run into a door that I didn't know was there, you know, those stories we all have, right? (laughs) But I invited him to come to my dojo and, you know, and since I knew all the instructors in the Bay Area he taught with Frank Duran and some others. And he loved it I mean because he, we had a huge welcome Hikituchi Sensei poster, and he came with his three Shihan as I recall, Tojima, Yanase and Anno Sensei, who I dearly love, the most wonderful unbelievable men. They somehow had three different perspectives on aikido and they would come over and sit with us and we'd have coffee and we'd go out of town and visit a shrine, which I never sort of had time to in Tokyo because I was running to the damn university. But so he came and I was just toward the end of my university career, for various reasons, and my interest in spirituality and psychology was seen as unfortunate.

Guillaume Erard: The fact that you brought spirituality in the academic environment, was that the issue?

Robert Frager: Yeah I mean I did, I invited Ramdas on campus, I invited Zen monks and Sufis. They claimed that it was an innovative campus open to all these things, but it wasn't. Truth was that was a lot of rhetoric and the guys who had tenure were all from Berkeley and UCLA. If I realized that I knew how to play that game I might not have chosen to, but I knew exactly how to do that. I understood that, you know, write a lot of stupid articles in a bad book at least.

Guillaume Erard: I've looked up the some of the publications that you had early on...

Robert Frager: Oh God... (laughs)

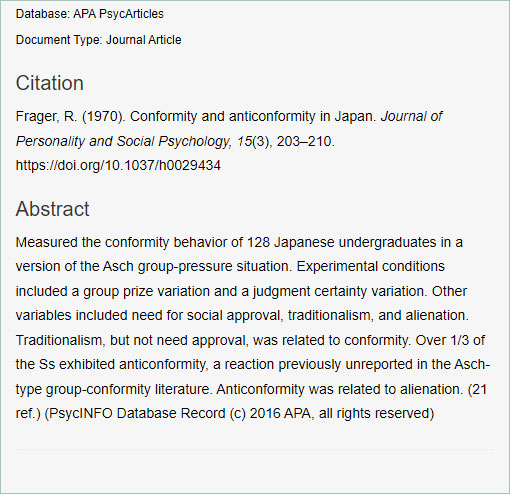

Guillaume Erard: It looks like you studied the Japanese psychology and especially with regard to conformity. Living in Japan, this is something that you struggle with, trying to find your place and trying to fit within a certain environment and its idiosyncracies. But at the same time you see some obvious people who do stick out and they seem to be doing rather well as well. In a nutshell what did you take out of that study? Did it reinforce some preconception, or did it change the way you looked at the Japanese people in general?

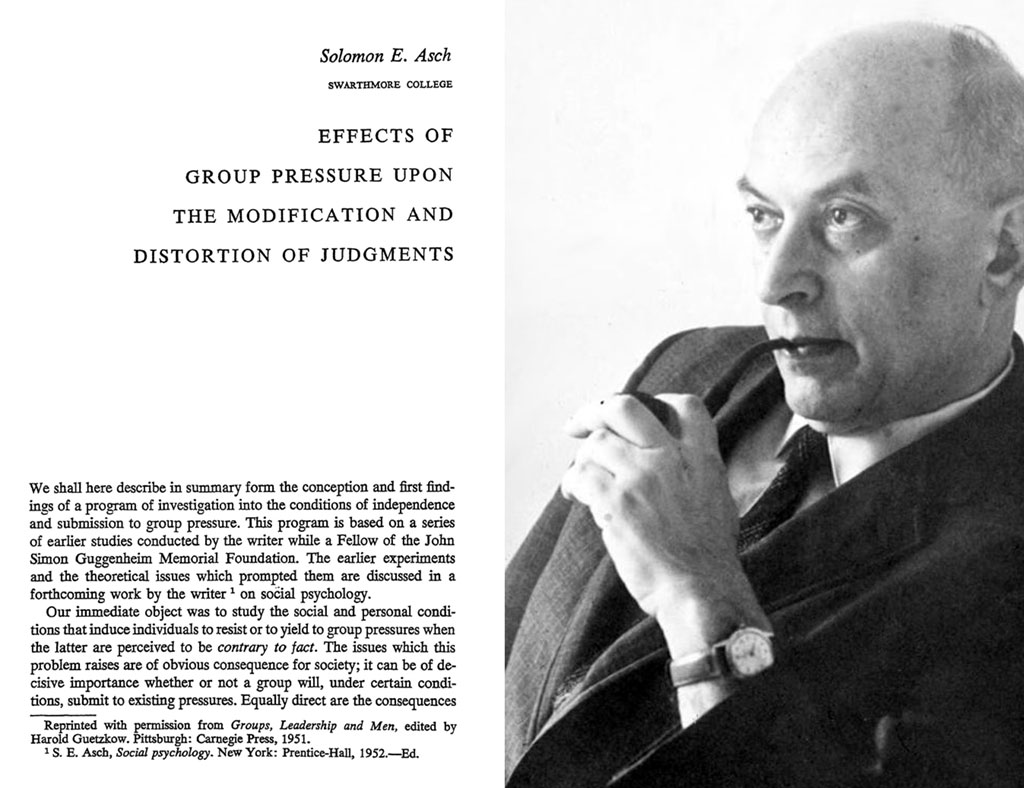

Robert Frager: Well I sort of had a minor in anthropology throughout my undergraduate and my graduate work. I read all the authorities, sociologists, anthropologists, and they all say Japan is a shame culture it's a huge conformer culture blah blah blah. You know, I'm really a trained experimental psychologist, and that was just armchair philosophizing. I wouldn't even dignify it by calling it theorizing, so I decided to replicate a very famous study by a man named Solomon AschAsch, S. E. (1951). Effects of group pressure upon the modification and distortion of judgments. In H. Guetzkow (Ed.), Groups, leadership and men; research in human relations (pp. 177-190). Carnegie Press. on conformity, which he did in the 40s early 50s.

And I ended up working with a wonderful professor named Stanley MilgramStanley Milgram (1933–1984) was an American social psychologist best known for his controversial obedience experiments, which demonstrated people's willingness to follow authority figures, even when doing so conflicted with personal conscience., who became very famous for his work on conformity. He was brilliant but again, he broke the envelopeIn Milgram's experiment, subjects believe that they are taking part in a study of memory and learning. Subjects are asked to teach word associations to a fellow subject (who in reality is a scientist) using methods including administering increasing electric shocks to the learner....

Stanley Milgram posing with his "shock box"

Stanley Milgram posing with his "shock box"

Guillaume Erard: He certainly did! (laughs)

Robert Frager: On the other hand his research was worth something and most of the stuff in social psychology was games. Stanley did his dissertation on conformity in France and Norway, comparing them, so he was interested in what I was doing. And I ran the classic Asch conformity study. I also gave a test of traditionalism, which I found or may have made up, it's been so long ago I don't remember (laughs). And a test of alienation which had recently been developed, and which I translated. I found something very strange, which I didn't know how strange it was. I came back with all the data sort of under my arm to analyze it when I was back at Harvard and it turned out that almost a third of my subjects, at least once, gave the wrong answer when the group was right. Nobody had ever found that before.

Guillaume Erard: Not to such an extent?

Robert Frager: And Stanley, who was a great experimentalist looked at me said "You know Bob look using Occam's razor we can explain your result by the fact that you screwed up somehow. You know that you're a foreigner and you scratched at the wrong time or whatever." And he said "I don't know that we can pass your dissertation." That was a great moment (laughs).

Guillaume Erard: I know exactly how it feels! (laughs)

Robert Frager: And luckily I had some correlations with a couple of tests I gave the subject and I had interview data which I'd recorded also. And as you know the Japanese are incredibly complex. Once you think you understand some simple-minded thing, you find out the exceptions.

Guillaume Erard: Exactly (laughs)

Robert Frager: And then you have people like O Sensei who don't care anymore. (laughs) And talk about DeguchiDeguchi Onisaburō (1871 - 1948) was one of the leaders of the Ōmoto religious movement, which believes that the original kami founders of Japan were driven away by the kami of the imperial line. This and his extroverted personality placed him in opposition to the authorities at the time and resulted in his imprisonment. Deguchi was also the spiritual guide of the founder of aikidō. He notably instilled on Ueshiba his universalist ideals., talk about not caring. You know, "let's bust the society open".

Guillaume Erard: But you talk about traditionalism, that's what gets me whenever I hear somebody — not even somebody who's met O Sensei — claiming to do "traditional" aikido. What is traditional? Aikido is a modern martial art and Ueshiba Morihei was all but a traditionalist in the way, as people have testified, he behaved and and taught, especially later in his life.

Robert Frager: He was a traditionalist by wearing a kimono when no other man did.

Guillaume Erard: Yes.

Robert Frager: You know he would have geta or zori and he would zip through the crowds. Gozo ShiodaShioda Gōzō (1915 - 1994) was one of Ueshiba Morihei's most senior students. He founded the Yoshinkan style of aikido. did a wonderful interview in that book Aikido Pioneers and in his autobiography, and he understood O Sensei better than most of the other pre-war students which is strange because everybody puts him to the side as though he just teaches police. Well and the fact that even when he was new uchi deshi, he was the guy who would take on anybody who came into the dojo for a lesson. But he said things about O Sensei like "O Sensei was never predictable, he was so fluid you'd never know what he'd do from one second to the next" and that's takemusuTakemusu (武産) refers to Ueshiba Morihei's ideal of what the ultimate martial art should be. It is an art where free techniques can be executed spontaneously and which harmonized all living beings., right, it's not one, two, three, four. I think it was NakakuraNakakura Kiyoshi (1910 - 2000) was one of the greatest kendōka of his time. Nakakura married Ueshiba's daughter Matsuko and was legally adopted into the Ueshiba family, where he was groomed to become Ueshiba's successor as head of aikidō....

Guillaume Erard: The great kendoka?

Robert Frager: Yes, he said "I quit aikido because I knew I could not understand O Sensei. I had no hope of getting to that level, so I couldn't stay." And I think people forget that. That's a very powerful statement. You're married to a Sensei's daughter, you're the heir apparent to the whole school, if you will, and he was such a sincere, such a great martial artist. You know, he was comfortable as an almost unbeatable kendoka, but he couldn't. He said "I couldn't get to the level of aikido that really is aikido." I remember, Sugano Sensei said "only one person knew aikido and all the rest of us are trying to figure it out or figure him out." You know so there are a few powerful statements like that, but you're right.

I remember somehow I had a friend a Japanese American friend whose wife was studying pottery and we went to a gathering of potters and they were amazing. They were they were like American entrepreneurs, they weren't caught by the society, they had their own little workshops the better they were the more they sold. I mean it was really refreshing to be among a bunch of Japanese who weren't so uptight. I think people also say if you go to western Japan the culture is far more free like that, but I never made it.

Guillaume Erard: Well that's the thing. In my particular case, my vision is so biased towards the the Kanto area and to the point that I travel to to Osaka, exit the Shinkansen, and experience cultural shock just by the way people look at me, or the way they're standing on the wrong side in the escalator. That tells you how much you're conditioned within a certain environment. To a large extent, there's a lot of the environment that conditions you, but you condition yourself as well. And and when you try to see through it, as you said, you think that you figured it out, and you look a bit closer and then you realize that no, you don't you don't get it.

Robert Frager: Yeah.

Guillaume Erard: Traditionalism comes up in Japanese conversations, but when you dig a bit you realize that things are an "invented tradition" most of the timeInvented traditions are cultural practices that are presented or perceived as traditional, arising from the people starting in the distant past, but which in fact are relatively recent and often consciously invented by identifiable historical actors. The concept was highlighted in the 1983 book The Invention of Tradition, edited by Eric Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger.. They call something "tradition", but if you dig a bit it's there's nothing traditional about it.

Robert Frager: Yes (laughs).

Guillaume Erard: For instance, the uniform, the hakama, all that stuff. And then you end up, which is the the end of all discussions: "But that's the way we do it". Okay then that's it, I guess.

Robert Frager: Yeah, or "it hides our footwork".

Guillaume Erard: Right, right.

Robert Frager: Instead of saying no, it was chaps in the old days.

Guillaume Erard: Indeed exactly, right exactly. I actually wrote an article on hakama when I got my shodan in Daito-ryu, and most Japanese people had no idea.

Robert Frager: I did my postdoctoral research knowing that there was a negative correlation between traditionalism and this anti-conformity. I got a whole group of subjects who were members of the Keio Kendo team. And what I found was instead of a third of them going against the group, maybe it was a quarter. There's a smaller number, but it was a hell of a lot more than nothing. You know, I called up Asch, who was the one who developed this, he'd retired already. I said "did you ever have this?" He said "not really I think once or twice people made mistakes." But it was not going against the group.

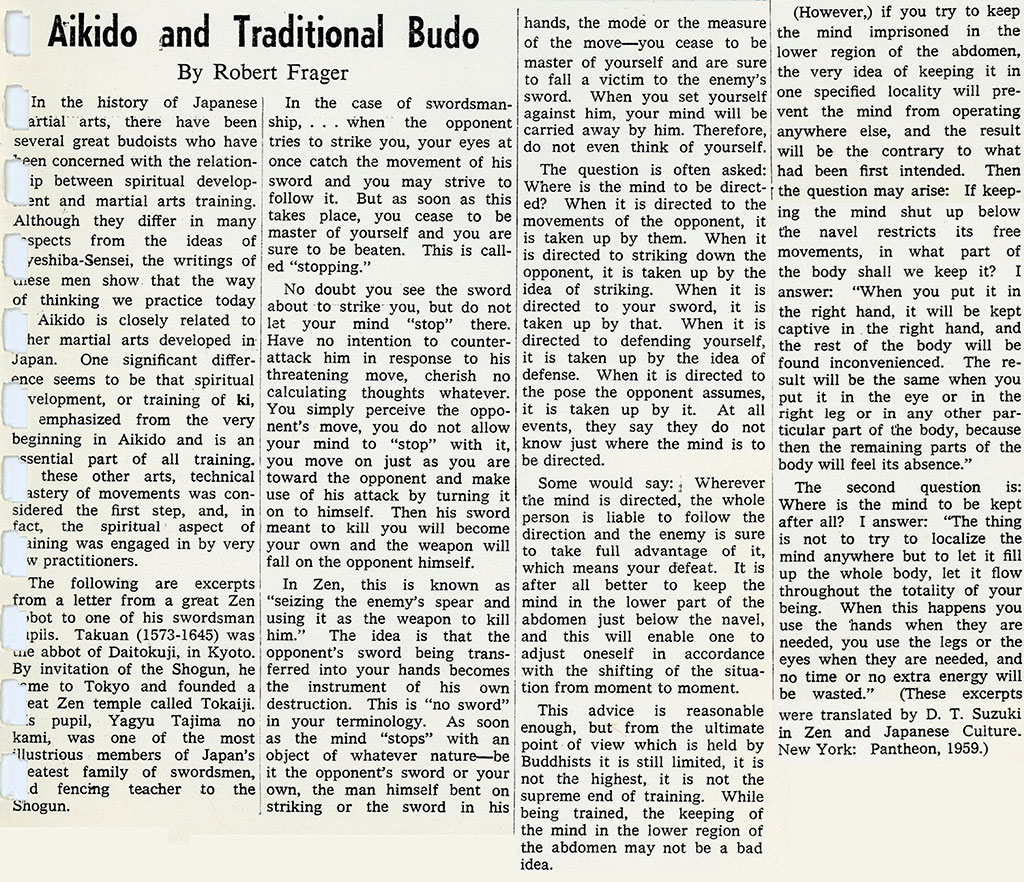

Article on Aikido and traditional Budo written by Bob Frager published in the September 1967 issue of the Aikido Newspaper

Article on Aikido and traditional Budo written by Bob Frager published in the September 1967 issue of the Aikido Newspaper

I've thought about this a fair amount since and had I really wanted to be an academic, I could have made made my tenure and gone to sleep for the rest of my life. There's a problem with the word conformity or traditionalism. Now the usual explanation is Japanese society pretty much puts a gun to everybody's head and says, "you know, if we fire you you'll never get a job at another company". It's almost like branding your forehead with something. And so of course, people are conformists, and if you assume that's somewhat true, then this counter conformity or anti-conformity is a reaction against that. I mean people sit and take it, and take it...

Guillaume Erard: It's all or nothing, isn't it?

Robert Frager: And then they explode. You know, and so there's a certain amount of that explosive rebellion that goes on in Japan. And so that's one level of explanation, but I think another level is, it's not even conformity if somebody puts a gun to your head. If you choose to wear a tie of the right color, that's your choice and we could argue that that would be a sign of conformity. But if I go into your bedroom and hold a gun to your head and say "here's the tie you need to choose" you're not being conformist.

Guillaume Erard: Yeah you're being rational! (laughs)

Robert Frager: Right! You are, it's a rational choice. I could demonstrate and get against that and be killed, and I think there's there's some of that that. We confuse a description of behavior with a description of personality, which is a problem in psychology. Had I wanted to do that, I could have spent a lot of time in my career distinguishing between personality traits and behavior, because there's not a one-to-one correlation. Freud even said years ago that all behavior is over determined, so you can't come up with a single determinationAccording to Freud, conscious experiences are potentially influenced by an unlimited number of experiences a human being has had, including events that cannot be remembered. Overdetermination describes multiple, independent, and concurrent causes of a psychological experience and is detectable not only in conscious thoughts and experiences but also in formations of unconscious processes such as dreams or neurotic symptoms.. So that's some of what I've I've thought on the basis of that research.

Having met people like Tempu, he was certainly one of a kind. You know who he was? He was the son of the senior samurai of one of the clans. So his father was the the equivalent of the CFO, I suppose, and I'm sure there's this is Japanese term I just don't remember. But there are a lot of those. Think of how many clans there have been, how many sons of the daimyo and sons of the other senior samurai, so there were a lot of people, and then there are people that rise to be heads of temples or heads or shrines, or there are a lot of places where people can rise above the system because they get to the head of it in one sense.

Tempu never got to the head of the system the way like a Buddhist abbot would, but he he was smart enough, he was an extremely businessman after he traveled abroad. The way he tells it, he said "look I made a lot of money, I would go out in the afternoon to places with hostesses and geisha and have a good time in the evening. But I got bored."

Guillaume Erard: There had to be something more to it...

Robert Frager: Yeah. He said "finally my wife told me to talk to her friends about the things I've learned and the things that made me into a different person" and he was so personally inspired by the experience of teaching and inspiring others that —well he did a very interesting thing and sort of very Japanese— he gave all his property and wealth to his wife and children and he said "I kept enough to keep an office in Ginza and enough for lunch for a year, if I don't make it in a year I'll just go back home." So every day, he got out in Hibiya park and he stood on a soapbox or whatever they did in Hibiya park, and slowly but surely he attracted people, and some of them had a lot of influence. And then people would come and talk about this in detail in his office with him. He built a society to where eventually, he became for lack of a better word spiritual tutor to the imperial family. But if you think about it that's not traditional at all.

Drawing of a Daruma by Nakamura Tempu, which he gave to Robert Frager

Drawing of a Daruma by Nakamura Tempu, which he gave to Robert Frager

Guillaume Erard: No. Time and time again you see that the Ueshiba Morihei story is strikingly similar. He had no claim to status or ancestry, or anything like that. They were land owners, they just had financial means. He went off his way and took things, technically, and then made it his own with little regard for lineage. The way O Sensei lived his life, I don't even know if we can even talk about developing a system per se. The way the Aikikai functions nowadays is a very different thing compared to how things were when he was around, and I was wondering if there had been a turning point in terms of that non-conformity in O Sensei's ways, and whether it was at odds with the fact that if aikido had to be passed on. To develop it, they had to adopt a more systematic approach. Nowadays, the Aikikai, functions exactly like any other Japanese entities that have been involved with. It has its own sort of idiosyncrasies but, in large, the same knee-jerk reflexes occur in specific situations. I'm really curious about what was the group dynamic at Hombu at the time as an organization and as a group of people?

Robert Frager: Well as a beginner I knew nothing. As shodan or nidan, I knew very little more. For instance, I didn't realize the tension between Tohei and Kisshomaru. I didn't realize how Yamaguchi had his own little world that was very difficult to get into. There were undercurrents, but I would go and I somehow moved from Saito Sensei, who was such a wonderful teacher and so generous, and was great up until shodan and even for a while later. And then more and more, I appreciated Osawa Sensei, but I also trained with everyone.

Osawa Kisaburo relaxing after class

Osawa Kisaburo relaxing after class

And I didn't know enough to choose a teacher to have that one-to-one relationship with, because Hombu Dojo, in a way, on the surface, everybody trains in every class and lots of different styles. The smart people say "I have to go to a private dojo and really learn" and that happened for me after two and a half years at Hombu. So it was two years solid, then I went back to the US for nine months, and then went back to Japan for post-doc research stayed almost six months, and then seven years later I went to Shingu and that's where I found it.

Guillaume Erard: Did you voluntarily refrain from associating more particularly with a given teacher or group, or is it just what happened when you were in your first stay?

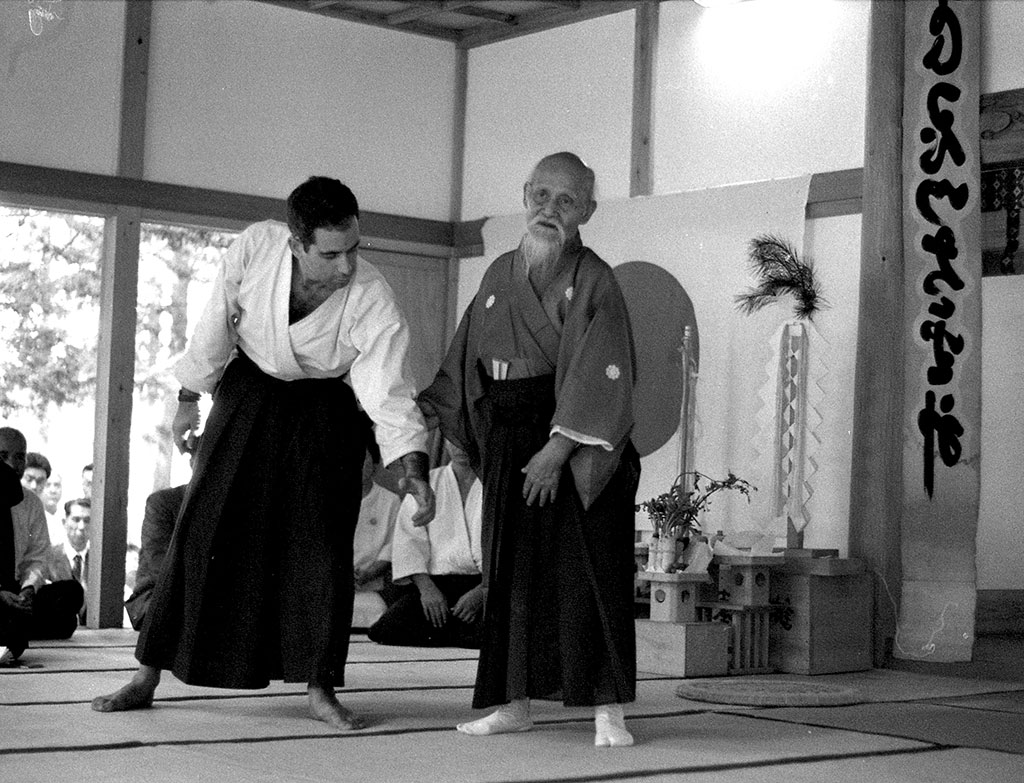

Robert Frager: Well, I think an awful lot of people knew that I was a student from Harvard, the only university in the world that the Japanese knew about, because of JFK. I asked O Sensei some time in the first year, "May I take ukemi for you? I would really like to experience your aikido." By then, I was fairly fluent and it was probably understandable. And there was this veil of silence like a thud. It's so horrible, you know, boom. And I said to myself "You just did it again Bob, you just blew it, you're the bull in the china shop again." He didn't say a word and I crawled out of his office. And as soon as I got my shodan, he started using me as uke. It was a wonderful lesson. He didn't have to say anything. It was sort of "I can't trust you not to hurt yourself or fall after me or whatever." And so it's pretty obvious among the foreigners I was almost the only one who was chosen for uke. I took ukemi for him at the aikido shrine the next year.

Guillaume Erard: There are pictures of that, right?

Robert Frager: Yes. And guess who was uke before me? Saotome. Usually, only the uchi deshi do this, as this is the aikido shrine. It so happened that I went up early because I had a flexible schedule, so I went up on Friday, with a couple of guys from Hombu. We swept out the dojo and cleaned things. And one of them was Kato Sensei, who I would train with as the strongest guy on the mat, basically. There are horror stories about what would happen if he didn't like you. The next day, I was in my keikogi and we were sweeping and watching the festival . He threw another uchi deshi, he threw Saotome and then he went "Come on!" and that was it.

Bob Frager taking ukemi for O Sensei at the Aiki Shrine in Iwama

Bob Frager taking ukemi for O Sensei at the Aiki Shrine in Iwama

Guillaume Erard: Interesting. So you're the one of the only other foreigner I've seen taking ukemi for O Sensei. There was also Terry Dobson, of course.

Robert Frager: Yeah, well because there was almost nobody there. I had Harvard, and he had six foot three of muscle. I think everybody knew my Japanese was much better than anybody else's except the second or third generation Japanese. And I would go places with O Sensei and sometimes or take ukemi for him, and so in a weird way, I was sort of beyond the grab of a regular sensei. Although I did go to Iwama, I did train with Saito. In fact, I have a picture of me walking with Saito's little daughter holding her hand, walking through the forest right in back of his house. She's very cute.

And well it's interesting. I trained with Kato Sensei and then he came here. Linda Holiday from Santa Cruz invited him to teach and she said that—she has very good Japanese—she said "Kato Sensei please do not injure my students." He laughed. He said "I don't do that anymore."

Guillaume Erard: "Anymore"! (laughs)

Robert Frager: Well, yeah. (laughs) In fact one of his big jokes with me, he said "I was always very nice; Bob-san was the rough one" which was so not true. (laughs)

But one of the things he said that was fascinating was "You know Bob, you and I were not deshi of O Sensei's, we were shinjaO sensei no shinja (大先生の信者) would translate as someone who is "a true believer in O sensei's teachings". of O Sensei." You know, and I'd never heard that word before or since. I mean, I know there are contexts, if you know you're a student of a religious teacher I'm sure, but he really had us put in that very special category of being his spiritual disciples, if you will. So I was in this...

I could have tried to take classes outside of Hombu. Actually, within those two years, Tohei came back, the triumphal Tohei. We can tell stories when we're not recording perhaps. (laughs) And he started teaching classes. He had a friend who was a judo 9th dan I think, who had a dojo right by the park in Ichigaya. He gathered the foreigners there because he wanted us to be his deshi, and that's where they trained. Terry Dobson came for much of it, I think Alan, Virginia, Ken, and others. But that was a special class and I was already gone. I mean, it was too late. I was already nidan at Hombu by then and I appreciated Tohei and I used his stuff a lot, which I think were great explanations, but I was also by then a direct student of Tempu.

Group shot from Tohei Sensei’s class in Iidabashi Dojo (Front row: Second from the left, Joe Deisher, fourth and fifth from the left, Tohei Koichi and Henry Kono. Back row: From the left, Ken Cottier, Joanne Shimamoto, Per Winter, and Alan Ruddock).

Group shot from Tohei Sensei’s class in Iidabashi Dojo (Front row: Second from the left, Joe Deisher, fourth and fifth from the left, Tohei Koichi and Henry Kono. Back row: From the left, Ken Cottier, Joanne Shimamoto, Per Winter, and Alan Ruddock).

Terry was the only other foreigner who would had gotten that close to Tempu except that he sort of dropped out of that. I was there all the time. And he sort of anointed me as someone who could teach his system in the West, which I did mostly to aikido students. I don't know, I'm going all over the place... (laughs)

Guillaume Erard: I don't know, at that stage, we're going to have to do a part 2 or 3 of this interview! (laughs) Talking about spirituality, you started as an academic, and then, I think you became more interested in spirituality. It must have been very difficult to understand O Sensei's spiritual speech. Were you ever interested in looking into Omoto and then reading the Reikai MonogatariThe Reikai Monogatari (霊界物語, Tales of the Spirit World) consists of a total of 81 volumes (83 books), which Deguchi Onisaburō created using dictation. It is considered by Ōmoto's devotees as Deguchi's most important work. or things like this?

Robert Frager: Well, no. (laughs) Two things: one is I didn't understand O Sensei's speech and I remember some Japanese people—it may have been my trip to Shingu or whatever—and someone said, "Did you understand his Japanese?" and he relaxed when I said, "No, I really didn't." And in fact I didn't understand it at a level at which I just watched. I didn't try to understand it but I came to understand a lot by watching, right? And he took a deep sigh of relief. And I learned from O Sensei in ways it's very hard to talk about—the way he did aikido, the way he treated his uke, the way he treated everybody. After I became a favorite uke, if you will, I realized every time I got up I had the same experience of not understanding what the hell had happened. I mean, I finally came up with the word "bewildered."

Guillaume Erard: Well, that's the thing. As you know in the Japanese traditional... here is that word again... (laughs)

Robert Frager: (laughs)

Guillaume Erard: Conformity plays an awful lot of role in that. And to what extent does the student fall due to the fact that those are these expectations of what should happen, and to what extent is the fall just what happened? I've been studying aikido for a while in different places and koryu jujutsu too. And in so many cases, what I see happen is the product of some sort of mutual conditioning between students and teachers. Yet for sure, based on statements of people like yourself or people who took ukemi, it's a different thing that happened with O Sensei. But words don't seem to be able to effectively distinguish the two phenomena.

Robert Frager: They don't help.

Guillaume Erard: No, they don't help.

Robert Frager: So eventually this fascinating thing happened. I would get up, going, and my feeling was... O Sensei of course never said what you're supposed to do and I would try to use my intuition and I thought, "If I do an attack he doesn't like, he'll do whatever he wants." And it felt like I would do a shomen attack and I would go right for the center of his head and I would swerve at the last minute and fall down. And he would stand there sort of quietly laughing inside. So I would do it again. I would say to myself, "I love this old man, I love him dearly. I'm going to give him an honest attack because it's not—he deserves it", then I would go off to the side.

Guillaume Erard: So to some extent you're blaming yourself like "Obviously I didn't attack correctly" or...

Robert Frager: Yeah, it felt like it. And then he said, "Sit," and we sat facing each other just like this. He said, "Put out your hands," which I did and he put his hand over both of my wrists and it was this lovely soft touch. It was a soft hands of a lovely old man and he said, "Push." Not only couldn't I move, I couldn't push, but there was no pressure on my hands. It was like a feather. It was a feather-like pressure and I couldn't move. It's like a hypnotist tells you you can't lift something.

Guillaume Erard: Right.

Robert Frager: That's pretty much what it felt like. And I thought, "Oh what he's telling me is no wonder you can't figure out what's happening. You're attacking at speed and whatever I'm doing to you is too subtle. Look, when you're sitting here with nothing else going on you still can't figure it out." And I thought about it a lot and talked with lots of people. I do think there's something about the ability to be so conscious of your uke and your flow of intention, your flow of ki, all of the above blend so well that it doesn't feel like an alien force coming into the system. You've now blended so well that it does feel like they did it to themselves. Because so much of the time we do this and you know what that is, but if we do this you may not. So that's what I sort of figured that out some decades ago.

And more recently I must admit I'm convinced that one of the great secrets of O Sensei's level of aikido is absolute concentration. And I try to teach it to my students—they can't learn it. They can't. I mean I think you have to get to some level in yourself to really be able to do it. And part of that's years of spiritual training of various kinds, that you have to put your ego completely out of the way. You have to put your self-esteem, yourself, and just be there to do what is called out by the moment.

And I just thought last night. There was an old practice, and I forget who taught it at Hombu. It was in class where you face your partner and you both have bokken, and it could have been Saito Sensei. And you bring your bokken down into ushiro geidan, like a tail, and you bring it up to the middle. And the practice is you're both in the exact same mirror position and whoever goes first loses. And I think that's an illustration of this point which is: if I'm absolutely concentrated, the moment there's any sense of movement from uke, if you will... Uke didn't quite work does it? I can match that speed plus a little bit more. And it doesn't matter how fast you try to go because you're telling me what speed you're going with so I can always do...

Guillaume Erard: Do you define who is uchitachi, who shitachi during those exercises, or those two have undefined roles and the timing comes when it comes?

Robert Frager: I've done lots of workshops with people that don't know much. You can do it either way. You can do it with a defined attack or with both of you sitting there. It's a great—that's more difficult—and it's a wonderful practice.

And I was reflecting on this today. There was a wonderful aikidoist, again total non-conformist, his name was Hine-san from Shingu. He was white belt for years. He refused to take an exam and he would beat the crap out of shodan and nidan who would come visiting Shingu. Now Anno Sensei liked that, but finally he said "Enough. You will take a shodan exam next month or I'll throw you out of the dojo." And so Hine did—he had no choice.

And I remember Jack Wada who's spent a lot of time with me in Shingu, and Jack said, "He's the scariest guy, almost, I've ever trained with." Now that would include Tojimura Sensei, YanaseYanase Motokazu (1931 - ) was a long-term student of Hikitsuchi Michio in Wakayama.... "because he's so damn fast". And I remember training—and I relied more on speed than muscle— with Hine and we were close, and he would come in fast, I would come a little faster, and he would come a little faster and I would come a little faster... We had an unbelievable practice. As you know, you're like on a tightrope. And that was the clearest I've ever come to doing that, this sort of concentration in a sustained way. And it was very special. It was almost like a different state of consciousness.

Guillaume Erard: It sounds to me like hierarchy and grades, dan and so on, go against that idea of letting go of the ego. When I started Daito-ryu, I had no intention of taking grades because I was already sick of what happened in aikido and so on. I didn't want that to poison my practice and I was very happy with my white belt. But just like what you explained, I've been told after a while, "You've been here, we've given you some knowledge. You need to take your dan examinations or you're going to have to leave." And just at the moment where I felt free and able to learn and enjoy without any pressure of any sort, the whole thing fell back on my shoulders. And of course you get to take the grade and then once you've got that, you got responsibilities.

Robert Frager: Yeah, I remember as soon as I put a got a hakama, one of my friends said, "We have to work a little after class and clean up your ukemi. You're shodan now." One of my Japanese friends. So yeah.

And I think in America it's the same, we just don't notice it. And I assume in France it's also the same. In fact, I know it is, since I did spend one wonderful summer in France with the family years ago.

There was a piece of research done about stereotypes that Americans have of Japanese and Japanese having Americans, and you know what? They're the same. At one level the Japanese all say "Well the Americans say Japanese, they're so polite. You never know what they're gonna do. You never know when they're gonna bow." And the Japanese say, "These Americans, they're so...you never know when they're going to stick their hand out."

So I think most societies run by a certain kind of traditionalism. There's a wonderful story about Carl JungCarl Gustav Jung (1875 - 1961) was a Swiss psychiatrist and psychoanalyst who founded analytical psychology. Jung's work has been influential in the fields of psychiatry, anthropology, archaeology, literature, philosophy, psychology, and religious studies.. What's fascinating is one of my first books was a textbook on personality theory—only book I ever made any money for, ever—and I wrote the chapter on Jung. So I researched and I realized all my professors had basically tried to brainwash me just like we were brainwashed into ignoring every sensei outside of Hombu Dojo. "Oh that Shirata. He has weird weapons work," or that stuff. Jung was a genius. He especially—if you're looking at full person development, spiritual, emotion—oh my God, he was incredible, really extraordinary. And I got to know a lot of Jungians, I even spent a couple of years in Jungian analysis.

There's a great story that he had his 75th birthday and his old students all clustered around to have a party for him. They're all sitting in his house sipping tea. And people kept coming and every time the doorbell rang, he would get up slowly because he had knees like mine, like all of ours right? And he would go to the front door and he would open and greet the person. And finally one of his old students said, "Professor Jung, please let us open the door for you. We'll be happy to do it." And Jung said, "Oh no no no no... answering the door to my house is the traditional thing to do. And I want to save my energy for more creative things." So that's a very conscious man saying, "If people expect me to wear a tie, I'll wear a tie because I don't care. And the amount of energy I'd waste explaining to everybody why I don't have a tie on is a waste of time."

Guillaume Erard: Do you think that's to some extent, the reason why O Sensei would have kept awarding dan? He didn't use the traditional system except—I mean he did award hiden mokurokuOld Japanese martial arts (koryū bugei) used the old license-based system while modern martial arts (gendai budō) use the dan system. Ueshiba Morihei initially awarded licenses in the menkyo system before switching mostly to the dan system. Note: There are however some records showing that he did award aikido hiden mokuroku scrolls into the 1960's. to some of them. But then he switched to dan. Was he just like "Yeah, just do your thing. Leave me alone. Get some grades and at least I don't have to explain why I don't do it." Do you reckon that would be some of that?

Robert Frager: Well, I was a witness to some conversations where old students would come in and they wanted rank. And he'd say, "You want 6th dan? Sure, I'll give you 6th dan. You want 7th dan? I'll give you..." He totally did not care. And he didn't care that it would make problems for the office, right? So even when Hikitsuchi would—and you know he usually drove them all crazy because he was proud. He was incredibly good and he studied everything. I mean he was really a gifted swordsman and was both a Zen priest and a Shinto priest, the whole business. And he was still crazy but... And again hiding behind traditionalism and something. But O Sensei did that with Abe Sensei too.

So I also remember Kisshomaru Sensei. When they come back, they're building the new dojo—the old dojo of course O Sensei hated the whole process because he had to stay at the local inn a couple blocks away—and he said, "I've given them enough money now that we can finish the construction." He said, "It doesn't matter. No, I don't care." I mean, it was just, the fact is one could logically argue that we needed more than one large mat space and there are lots of reasons to have a four or five storey building. But O Sensei sort of had this wonderful "I don't care." And again you remember Kisshomaru's biography of O Sensei where he talks about it... And there's a bitterness in there, yeah, for sure. He said, "What he put my mother through... She never knew if we'd have enough money for a meal next day." So that's the downside.

Guillaume Erard: From some of the research I've done, that's the image that I got. The unsung heroes of aikido. And people don't realize how much we owe to the extended Ueshiba family for being able to practice it nowadays, with Kisshomaru, his wife, his mom, his cousin...

Robert Frager: And I was lucky. I had several days in Iwama with, in a sense, just me and O Sensei and then the local country guys who would come in and beat me up for keiko every night. I was black and blue.

Guillaume Erard: They like to let you know that you come from the city, so you're a softie.

Robert Frager: I was complaining to my old friend, Tomita TakejiTomita Takeji (1942 - ) began aikidō in Tokyo in 1962. He then became an uchi deshi in Iwama until the death of Ueshiba Morihei in 1969. He relocated to Sweden the same year., who is a close student of Saito Sensei who started Aikido or was the head of Aikido in Sweden for years. I though: "God, are they beating me up because I'm a gaijin?" He said, "No, because you're a city guy."

Guillaume Erard: Exactly. (laughs)

Robert Frager: You know, and they're also working with their arms and legs all day long.

Guillaume Erard: From your interest in Saito Sensei's aikido, and then your study with Hikitsuchi Sensei, it's quite a leap isn't it?

Robert Frager: Well it was years apart. They were worlds apart but in a funny way, Yanase Sensei was more like Saito. He was a shorter version of Saito, who's short, somewhat wide. And he's the only person I would be afraid of ikkyo, because my head would go down so quickly I would have to whip my head around so my nose didn't smash into the mat. And there was no muscle. I was vertical and suddenly I was horizontal. I mean he had that kind of strength. So it was very much an incredible stamina. He didn't even break a sweat ever.

And then Tojimura of course was very martial, incredibly fast and very skilled with a sword. And we were close. He had a wonderful sense of humor like you'd pinned him doing gokyo-osae and he would just sort of sit up and stand up and walk away. I was like, "Wait a minute, wait a minute, when I pin somebody in gokyo-osae they don't get to do that."

And then of course Anno Sensei really brought something unique in my experience, which is his goal was to make the dojo a joyful place, not to show off how martial he could be.

Ueshiba Morihei with Anno Motomichi and Hikitsuchi Michio

Ueshiba Morihei with Anno Motomichi and Hikitsuchi Michio

So I was ready. I mean, it was just a very rich environment in those years. There was a rich environment at Hombu but it was different. I mean the three shihan in Shingu were very close and they often butted heads with Hikitsuchi.

Guillaume Erard: Let's talk a little bit about the practice in Shingu and what was specific about this and what made it so that you, after all that time, finally stuck to a teacher to a group?

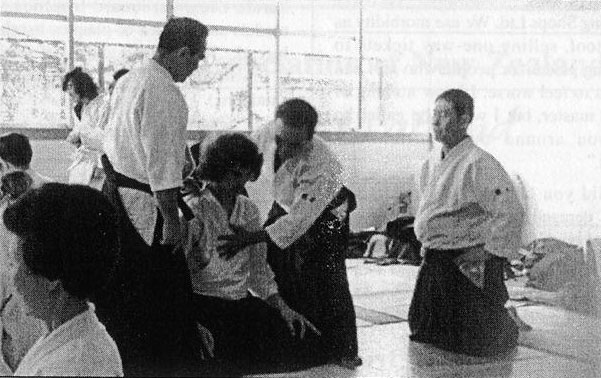

Robert Frager: Well I was, I really was struck by the fact that the dojo in Shingu felt like a whole, that everybody knew each other for years, all the instructors certainly, and it's funny because we used to talk about Hombu as a factory even then. Even then I mean you were talking about the 1974, that was late.

What was interesting was the style in Shingu included atemi but but not actually, normally not striking. You know you just show someone that there was a tsuki by pointing it out with a punch that came very close. There was one exception, there was one sensei who was not in Shingu itself, he had a small dojo and he was very intense. I think he was something like sixth dan at 27.

You know and he did a demonstration, there was a festival in his town so of course the local aikido teacher would demonstrate aikido and he started with kids and he had this great joyous kids class. They would do cartwheels followed by forward rolls, had a great time, he had a great time with them and then, it came time for his adults class which were four depressed men. Sort of "don't hit me again sensei" whatever, and we were friendly enough. I said to him, "Why do you, why is it that you have such wonderful happy children's classes and only a very few men?" And he looked at me and he said very seriously, he said "Well with the children I pull my atemi."

And it was true he would come to the Shingu dojo and, the very first round, —it wasn't not like Hombu,— you trained with different people in Shingu like many other dojos do. And so he would pick one of the young black belts. Within two minutes the guy would have a bloody lip or nose and then Hikitsuchi would use him as uke and beat the crap out of him, letting reminding him that sixth dan ain't tenth dan. So it was crazy. My experience in Tokyo was, we would train hard and it sort of didn't matter what rank someone had. You had to prove it to me on the mat. I think that's still there now, you know it's like "I'll do irimi nage and if you don't do it well I'll block you and then I'll do another irimi nage and now we'll know who's the sempai". But it became egoless in a weird way because if you were better than me then you're the senpai and I'll really study with you. Of course if you have one uke to work with then that really sets the tone for the whole hour.

So there was a lot of intensity and a lot more martial edge to Shingu in a way, especially Tojima sensei well and Hikitsuchi himself, even though I don't remember anybody punching me and I don't remember anybody really punching someone. And so when I went back to Tokyo I spent about a week, and I stayed in the apartment around the corner. And I was looking around and nobody was aware of tsuki, everybody was wrestling sort of, you know, there was a lot of physical "I'll make it work." In Shingu you'd never do that. I mean you'd start and if the guy resisted, you'd signal an atemi and then complete it, then you wouldn't punch them out unless they got obnoxious, I suppose. But I was looking and said to myself, "you know almost everybody on the mat I could take down", and I think I was probably correct. So I was looking around sort of disappointed, and part of it was, this was years after I'd started, I was a lot better. In Shingu I would often train with a sixth or seventh dan while the tenth dan was teaching the class so that again honed my heat up skills a lot.

And then all of a sudden I saw Kato Sensei. He never taught at Hombu, ever. They asked him to, but he refused. But the guy who introduced me to him, who was a tough younger black belt, called him Kato Sensei. I heard stories about him, so I always called him Kato Sensei. He was the only one not teaching that I called sensei, just to keep my body in one piece, but we sort of became friends. I mean, we trained together and it was almost like someone cast a spell on me, and I became my grandmother with the flu, nothing worked. "I could chin myself on your arm you know until you get bored, Kato Sensei." You know, he was so strong, technically so skilled, and I said "Oh shit, there are people like that here and I probably can't see half of them."

Bob Frager with Kato Sensei

Bob Frager with Kato Sensei

And when I went to Japan to pick up my seventh dan. It was sort of funny because we were walking to the train station after his class, so we're chatting, there's just the two of us were going to a restaurant by the train station and he said, "Well, you know you may not get it tomorrow." And I think, "I won't take this well, I won't be philosophical. I came here to get seventh dan, my son came with me and I showed him around Tokyo and it was fun and trained with." He said, "Hombu doesn't ever say yes, they will say no." It's such a weird system, I mean even for Japan. And then he turned to me and quietly said "But you know, the office at Hombu doesn't ever give me a hard time. They're all afraid of me." Just like that.

Bob Frager receiving the 7th dan from Doshu

Bob Frager receiving the 7th dan from Doshu

Guillaume Erard: You came so that he could recommend you for the seventh dan?

Robert Frager: Well he had recommended me.

Guillaume Erard: Oh, so you came for the kagami biraki?

Robert Frager: I came for not getting a yes, but it was pretty much a done deal. I think they wouldn't have, especially my coming that far, said "Maybe next year." So it was a different style at Shingu and it was more intense. And and we'd often train after an hour and a half class. You know and we had to be in pretty good shape to start doing aikido for a solid two, two and a half hours. But we were.

Guillaume Erard: Did you pick up much weapons over there? I would imagine you did.

Robert Frager: I picked up so many weapon styles it was coming out of my ears. I mean I studied weapons with Tohei, I studied weapons with Saito. I was even signed his registration book for Negishi-ryu Shuriken-jutsu. The guy who signed before me was Chiba KazuoChiba Kazuo (千葉 和雄, 1940 - 2015) was an 8th dan aikido teacher. Born near Tokyo, he practiced judo and Shotokan karate. In 1958, he was admitted as an uchi deshi to the Aikikai's Hombu dojo and began teaching in 1962. He lived in the United Kingdom and the United States, where he considerably developed aikido., so I was in a very select group. And so it was Saito and then finally was Hikitsuchi, which was closer to spear.

And then finally, there was Kato who was the best of all of them, which is fascinating. Kato learned by watching O Sensei and by training his butt off. The story goes that he would go at least one weekend a month, maybe more often. He would take the last train out of Tokyo to the end of the line, hike up into the mountains and train until the first train going back to Tokyo Monday morning. Something like that, I mean it's insane amount of training, that's how he was so good.

At one point, he was showing me how to really do a bokken cut and he was really going, "You squeeze and as you let go, the letting go will not let the bokken spring up." And he had an amazing way of holding the bokken sort of like this softly, no grab at all actually, all his techniques were like that and he really got me to understand that style of shiboruShiboru (搾る) litterally means "to wring" or "to squeeze", like with a wet towel. The image of wringing out a wet towel is often used to teach how to achieve a correct grip of a sword at the moment when a strike or thrust has landed. At the moment of impact the little and ring fingers should tighten around the hilt as the thumbs rotate slight and thrust forward. and he said to me, "You know if I hadn't learned that I couldn't have done 10,000 cuts a day."

Guillaume Erard: As you said, there are so many styles of weapons, and it's very difficult to trace back the weapons that O Sensei actually did practice, let alone used. And and it's even harder to to try to trace back the weapons before him. So in terms of how well pieces fall together in terms of weapon practice and what is supposed to happen consistently when empty-handed, do you have a comment to make on whether there is a particular way you do things that works better than others you've seen, in terms of that all-encompassing sort of consistency?

Robert Frager: Well I mean I would just let one style go when I moved to the next one. I didn't try to keep up the older styles. And there were these six or seven years where I would train with my best student every morning for an hour, Monday through Friday, in addition to everything else. My advanced classes were always an hour and a half. This is what Kato Sensei did - an hour of taijutsu and an hour or half an hour weapons, and so that was my routine has been for many years. Now COVID and everything else is, you know, sort of put a hiatus in that but that's basically it.

And he has a really brilliant weapon style that came from watching O Sensei. He said, "I didn't study anything else." And he has four basic styles in bokken, four basic styles in jo, and six variations within each - three omote and three ura, and they're all related I mean they really make sense.

Guillaume Erard: In his book, Ellis Amdur says that for the ken, the forms of Saito Sensei were closer to that of Kashima Shinto and the forms of Hikitsuchi Sensei were closer to that of Shinkage-ryu. Of course the link between Shinkage and O Sensei is a lot easier to see than Kashima Shinto. Is there a fundamental way of moving the body that differs in those two practices? You've experienced both systems. In other word, do you make other accommodations in your weapons to make sure that you move consistently?

Robert Frager: Well I'm clearest about Kato because that's the one I've done longest, and and he would come twice a year and every time he came I felt I knew nothing. You know and I'd go "I know nothing and I'm pretending to teach this stuff, how embarrassing." And he would correct me and you know in front of everybody and I went "Well this, this is good for my ego, it just got punctured again."

But I think all of them stressed basically turning and entering, you know that irimi is not a spiral, it's an entering spiral. Ura has a retreating spiral. And you know it was a famous saying of O Sensei, "You know in jujutsu in the old days when you're pulled you enter, when you're pushed you retreat." And he said, "No, in aikido when you're pulled you turn forward and when you're pushed you turn back and draw." Something like that and that's really the style of Kato Sensei. We used to joke that he had somebody implant ball bearings in the bottom of his feet because that's how he moved. It was just unbelievable how he would just scoot from side to side on the mat.

So that's what has stayed with me the longest, but I think they all have that in common except one. You know so often, I see people, you know entering right down the middle to stop a sword cutting block, and I go "How unbelievably stupid." I mean you never ever ever should do that. I see senior aikido do stupid things like that all the time, you know not pay attention to having a yokomen angle all the time. You know they would go straight or they would go right down the middle or they would sort of block and stop. I mean even Saito Sensei, there was I remember one of his moves where he would raise the bokken and stop and then move, and it's like no, it's one move, why there's no need to stop.

But you know I spent years working with Musashi's Book of Five Rings, ten years, twelve years, doesn't matter because I still don't understand it. And it's interesting because I was able to put one of the rings to each to different aikido teachers.

Saito is the easiest - the man's built for ground. And the fact that he will slip into stopping, is works for a ground stylist if you will. You know and he can settle and then give a stronger punch or movement whatever.

Water is really Osawa Sensei. Nobody understood Osawa Sensei's aikido either I mean it was so absolutely fluid. Anno was a lot like that.

Tojima Sensei was fire and there are some others like -- I'm not sure at Hombu if anybody had that much fire. Oh yeah of course Chiba, you know, the maniac on the mat.

Air - it's hard to find it in aikido. I think I did peg somebody but I, I'm not sure I can remember now. I also studied tai chi for a while. My tai chi master really puts water and air, you know and he had this wonderful capacity to show us a move, nice, and then, and for fighting and suddenly he blurred. And I could tell that he was this relaxed, this like someone speeded up the film. He was relaxed in the middle of that. He had been all Chinese kung fu champion in praying mantis style and his father was a tai chi master. But you know you sometimes I think should go outside of aikido to really see different style.

And there are a few, the only, there are some people that really move to emptiness, you know that last ring, mainly O Sensei.

Guillaume Erard: Having taken ukemi for O Sensei, did you ever take ukemi for other people where that ever came close to that same feeling that you had?

Robert Frager: Sometimes, Hikitsuchi had a version of it. I can remember once in particular where he did techniques without touching me but it felt like he cut my ki, my aura to shreds. Every movement was like shredding my energetic integrity, for lack of a better word.

Kato Sensei would would move in ways that were like, "what the hell happened?" And he was, he was not limited by a single style of movement or practice.

So in fact what was fascinating was I was standing beside the cameraman for the opening of the new Hombu Dojo back in '67 I guess it was. But there were, I think, four people who demonstrated, it was really really interesting. Saito Sensei demonstrated and he did nothing but basic technique, shomenuchi iriminage, ikkyo, you know and then he would throw someone two mats. So he was demonstrating the essence of basic technique without any bells and whistles. Osawa Sensei just flowed around and made it look easy. Tohei did his hops and bounces whatever. Kisshomaru did what he did, which was a new trend. Was he still alive when you came to Japan?

Guillaume Erard: No, I missed him.

Robert Frager: He was incredibly deceptive, unbelievable. It looked like he didn't do anything, you know he would do boom boom. And there were some occasions where I'd be backstage because I had gone on before as one of the gaijin of Hombu, so I would watch his uke who were all uchi deshi, they were just fine on stage. The moment they got on stage, I mean they were, you know normally these guys don't show but well he, he would nail though. He had an incredible nikyo, sankyo, that it really didn't look, he wasn't obviously putting power into it. And then of course O Sensei was on at the end and one of the uke, I think was Hikitsuchi, another one was Abe, not the artist, the scary Abe.

And it it was an amazing difference in styles, really extraordinary different if you think about it. And I think that was both an advantage and a disadvantage. Still is. I think there's there's less variation now in Hombu Dojo, especially after they sort of fired all the senior sensei and there were younger guys who were all identified as Moriteru's disciples, I think. And it made sense in a way that he did it, but I'm not sure. I don't know because as long as there are different dojos there will be different styles.

Guillaume Erard: There's quite some differences in in different dojos and the only thing is of course is that you have to be lucky when you register to a local dojo. You know it could be like, it could be pretty much anything so...

Robert Frager: Yeah. I literally heard Saito Sensei saying "We're having visitors, let them know this is the dojo of the Aikido shrine." It's awful.

Guillaume Erard: Well I think we've all gotten that, you know coming from Tokyo for the odd visit to Iwama. We had to deal with that sort of approach. Did you ever compare notes on your various evolutions in your aikido with other people that were there at the time? I mean especially in North America did you ever connect again with Terry Dobson or Henry Kono, or those people? Are you aware what they were doing afterwards?

Robert Frager: Well I connected with Henry and, you know we talked and I've invited him out here. We had a whole big aikido embu that I put on.

Guillaume Erard: When was that?

Robert Frager: Ten years ago.

Guillaume Erard: Okay so quite recently.

Robert Frager: Terry came up here and we were sort of acquaintances more than friends and he was busy up in San Francisco writing books and doing things. I hung out more with the guys who were local, which was Robert Nadeau and Frank Doran. But I was lucky because as soon as I came back, I started teaching at universities. I restarted the Aikido club at UC Berkeley. I taught there only for a year but that ended up with a successful dojo in Oakland. I then moved to Santa Cruz, I had a really large group of students there and started teaching sort of aikido workshops for both excellent and growth centers, things like that.

It's interesting in Los Angeles for example, there is Rod Kobayashi who was Tohei's deshi and for whatever he did, he just looked to Tohei. And when he went to Japan, he went as Tohei's boy, by the way that's how Steven Seagal went to Japan as well. He was still Tohei's guy, he admitted it to me I mean. And it's easy to figure it out. And then of course you know he took over his wife's family dojo, which was sort of under Abe's wing. But you know, I was independent because of having university dojos.

Tōhei Kōichi (left) instructing Steven Seagal. Ki Society Dōjō in Ōsaka (1974)